To my surprise this series of posts has become a love letter to collagraph as a process. I am going to keep following this direction, because I see the “atom level” aspects of process as being critically important to the construction of the social and discursive parts of the field. Collagraph is about access and possibility. It is about creative reuse of materials, and about embracing chance. Collagraph allows emergent form and dislegible texts, and it encourages beginners and experienced printers alike to find their own way through process. It can be a metaphor for a whole studio practice.

This post is technical. It gets into the details of how to make these ideas work and is structured around discarding some basic assumptions about letterpress printing:

YOU DON’T HAVE TO BE EFFICIENT AND YOU DON’T NEED A PLAN

You need a place to start, time, and a willingness to fail, to keep going, and/or redo things. Stay with the process of printing to see where it leads.

YOU DON’T NEED ACCESS TO EQUIPMENT

I am framing my descriptions here around the use of a cylinder or platen press, but I realize that unrestricted access to that equipment is not a given. I think that it would be possible to adapt many of these approaches to hand printing because they don’t necessarily rely on large amounts of evenly distributed pressure to print. In fact—hand printing might open up even more markmaking possibilities. We are already seeing this with so much pandemic-era printing at home. (See Erin Beckloff’s post from September 1).

THE MATRIX DOES NOT HAVE TO BE TYPE HIGH OR EVEN ONE CONSISTENT HEIGHT

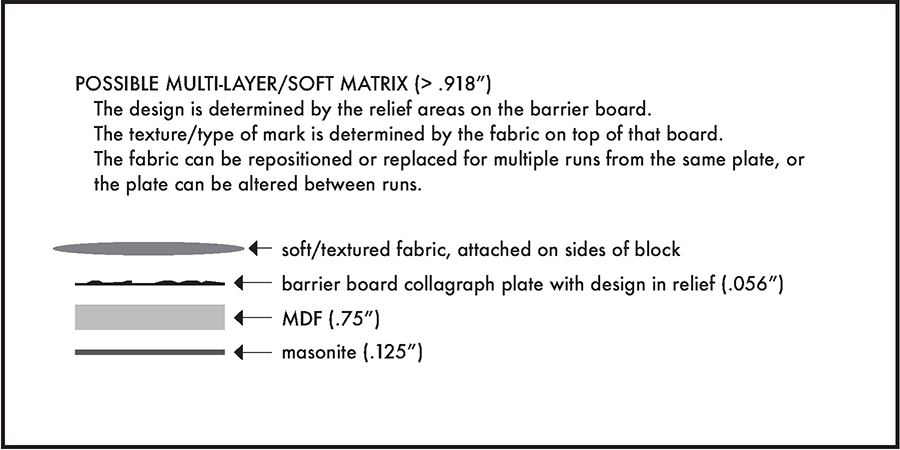

Variability in matrix height is one of the main ways to produce marks with variety. A lower matrix will catch less ink from the rollers and print with less force. A higher matrix will catch more ink and print with more force. In collagraph you can control the height and amount of relief on the block by adding or removing material from the plate itself. Height can also be adjusted by packing under the base block that the plate is attached to (or adjusting bed height if you have a press with that capability). This can also be done with a platen press—you can use a base block made of multiple layers, and add or remove sheets of paper between those layers to make adjustments to height. (More on the multi-layer base below.)

A single matrix can be printed at multiple heights to build up (or push back) color. A mark could be printed in one color, and then in the next run the matrix can be dropped in height, and printed with a new color. Building up color this way in painting is called scumbling. It produces a different color and surface effect than the layering of transparent solids and/or direct printing. There are other painting terms/techniques to explore in print-based markmaking: facture, pentimento, sfumato, impasto, manipulating edges, etc.

THE MATRIX DOES NOT HAVE TO BE STABLE—

or solid, or flat, or even, or consistent, or hard, or dry, or sealed against the ink, or composed of a single layer. The matrix is anything that can make a mark. A mark does not have to be pressed into the sheet—it can be brushed on, squeezed on, etc. There are so many possibilities—brush matrices, soft matrices, flexible matrices, multi-layer matrices, and things still to be invented. Matrices can be made to move, change, and/or decompose to produce a variable edition. A soft or flexible collagraph plate can produce marks of stunning delicacy and subtlety. Collagraph plates can also be made to glop ink on in impasto blobs. Dimension in letterpress can go both ways: into the sheet and coming off of it. (Pro tip: use oil-based inks or add cobalt free drier.)

A reduction process for linoleum or woodcut is great way to make multi-color prints. With collagraph you can use an additive process instead, or both additive and reductive at the same time.

YOU CAN MAKE YOUR OWN TYPE

The current remote teaching situation has shown that movable type can be a flexible and accessible material to work with. I am excited about all of the ways that people are combining hand techniques, digital design and fabrication, and what are essentially collagraph principles to make new type.

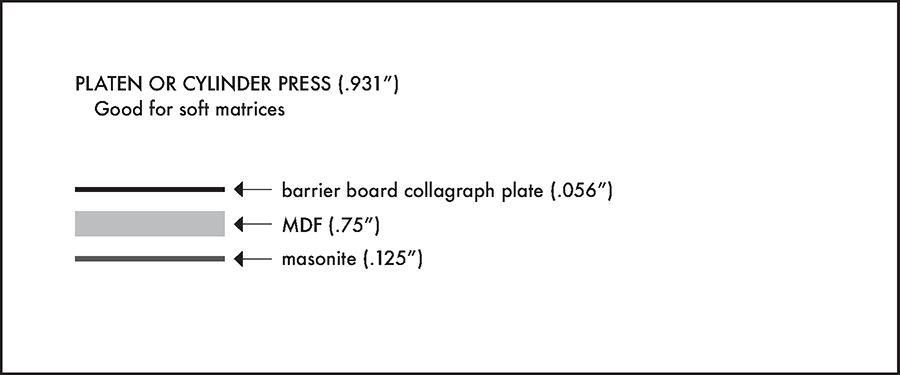

Here is a formula that I have been using to quickly get close to type high with blocks/type:

3/4 (0.75) inch MDF (Medium Density Fiberboard)

+ 1/8 (.125) inch masonite/plywood/acrylic

+ this barrier board from Talas (.056) inch

= .931 inch—slightly above type high (reduce packing on your press to compensate, and don’t be afraid to adjust the rollers too).

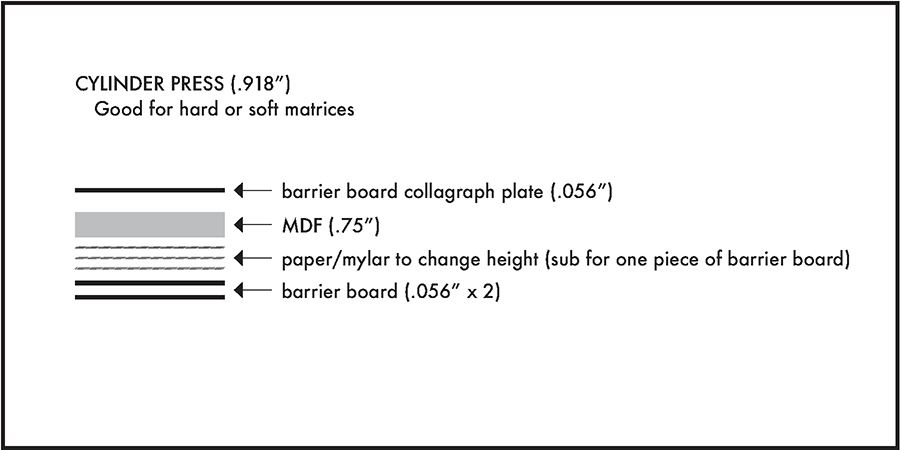

OR

3/4 (0.75) inch MDF

+ 3 sheets of barrier board from Talas (.056)

= .918 inch—exactly type high

The above layers can be combined to make a base block—the MDF and either the masonite or barrier board, and then the last layer is whatever is being used for the type. A multi-layer base can be used on a cylinder or a platen press, and layers can be further split or subbed out with paper to manipulate height. The letterforms can be cut out of the masonite or barrier board, by hand or with a laser cutter or CNC router. Stick them to the base block with Boxcar photopolymer adhesive or double-sided tape. You can have type that you keep and reuse, and/or type that isn’t precious and can be destroyed in the process. This type can be combined with the collagraph matrix ideas described above. Type, like any matrix, does not have to be solid and perfect and precise—but it can be—or at least precise enough.

“Precise enough.” That is really the point here—as the printer, that choice is yours. You don’t need permission, “proper” training or “proper” materials, and you definitely don’t need to follow a pre-determined aesthetic. You only need a vision and a desire to chase it. Do it all wrong, and keep doing it wrong until you push through the doubt and criticism—the field will be better for it.

Aaron Cohick (he/him) is the Printer of The Press at Colorado College and the proprietor of the NewLights Press. He lives and works in Colorado Springs, CO.