When I developed an interest in artists' accordion books I searched around for writings on the subject and found, with the exception of one very recent book (see Part 2 of this blog post), there is a paucity of literature on the subject. It was against this background that I started my accordion blog in 2010 in an effort to bring artists' accordion books out from under this cloak of invisibility and to document their fascinating and vibrant history.

With regard to that history, artists do not start using the accordion format until the early 1960s. From my preliminary research, the decade opens with an accordion by Yoko Ono titled Painting Until It Becomes Marble, which was collectively created by the visitors to her exhibition at the AG Gallery, New York in July 1961. This was one of her early 'instruction pieces,’ and aside from its beauty, it represents a radically alternative publishing model in which chance and audience participation are two vital ingredients.

The following year, Timm Ulrichs and Warja Lavater created their own very different accordions, respectively titled Fragment and William Tell. This early Lavater work establishes her pictographic style that would become a central feature of the accordions she created throughout her extensive artistic career. And, finally, let's not forget Etel Adnan who created her first accordion work in 1963 and has used the accordion format in her painting practice ever since.

The accordion book is a strange creature. Variously called an accordion, leporello, oriental-fold, zigzag, or concertina, it is a hybrid of the scroll and the codex, and it combines both the compactness of the traditional book and the expansiveness of the scroll. But it has one feature that neither of them possesses: when opened up, it reveals its sculptural presence.

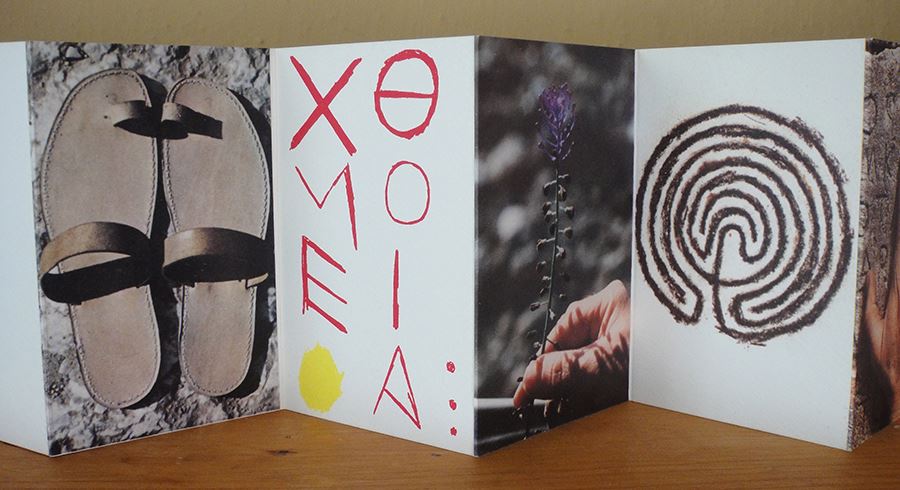

Joe Tilson, Proscinemi Oracles, Edizioni del Cavallino, Venice, 1981, ed. 200.

The accordion format improved upon the scroll by offering the reader a greater ease of access to different parts of the story or text. One commentator has observed that the scroll has “a sequential access format” and the codex has “a ‘random-access format.’” Notable features of the accordion that improved upon the scroll include the ability to use both sides of the page and its protective covers, which enabled it to be transported safely.

The accordion book is defined by one crucial and elemental feature, the fold. The fold gives the accordion not only its compactness, but is instrumental in creating the accordion's most pronounced attribute — expansiveness. In their open state, accordions fundamentally challenge the idea of the traditional book, and in a very literal sense they function as ‘expanded books,’ and they provide a space in which a richer play of texts, images and pages is possible than in the ordinary codex.

Accordions also offer the viewer a very different reading experience than a regular book. Moving beyond our ingrained way of reading from left to right, the accordion offers the viewer a flexible way of approaching the book that includes reading and scanning the book from right to left, opening it up and viewing it as a whole, examining the individual pages and turning it over to discover what's on the reverse. An accompanying feature in any encounter with an accordion book is the high degree of handling and physicality required of the reader in their interaction with the book.

The accordion format makes possible a huge variety of page pairings and sequencing across its length. At one end, there is the seamless panoramic space when fully opened, at the other, with one image per page, the accordion is turned into a mini gallery, all of this coupled with the many different combinations in between.

Accordions also question the role of the reader, interrogating whether they are simply ‘readers’ or whether they become ‘viewers’ when confronted by these often very long bookworks. Accordions, in their own unique way, collapse any clear distinctions between the two terms and their associated modes of perception. To read, or to view, an artist’s accordion is to engage simultaneously on a number of levels with a multi-faceted bookform.

Acknowledgements: "Scroll," Wikipedia search, 8.7.90; Leporellos, Etel Adnan, Galerie Lelong & Co., Paris, 2020; and Johanna Drucker, The Century of Artists' Books, Granary Books, New York, 1995.

Stephen Perkins is an art historian, curator, and artist living in Madison, Wisconsin. He is the curator of the home gallery Subspace.