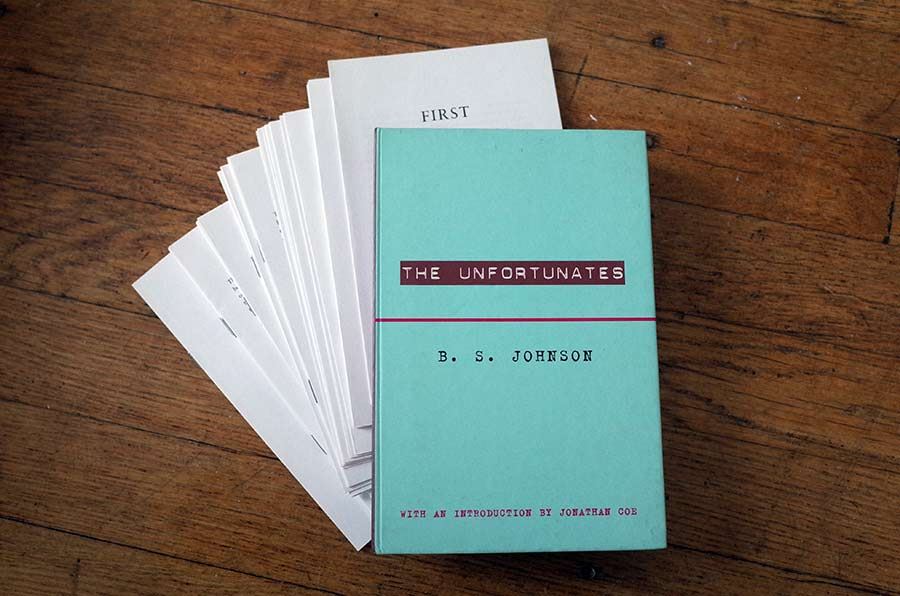

Within literature, the challenge to linearity has fallen in and out of favor, though it generally manifests through either writing strategies, such as shuffling narrative pieces out of straightforward time, or through formal strategies that challenge the physical constraints of the traditional codex. B.S. Johnson’s The Unfortunates is an example of the latter, in which the book cover is in fact a clamshell box that opens to reveal roughly 28 loose signatures that can be read in any order, with the exception of FIRST and LAST.

Linearity might suggest that truth can be revealed through a singular path. The hyperlink as defined by Ted Nelson [1], however, eschews linearity and in so doing posits that truth is instead positional. In his 1974 Computer Lib/Dream Machines, Nelson observed that, “the structures of ideas are non sequential” and offered the hyperlink as a means by which a user can be presented with alternatives to conventional hierarchies.

Within 25 years of Tim Berners-Lee’s contribution of the world wide web in 1989, two in five adults on the planet have been initiated in Nelson’s hyperlinking. Much has been written about how the internet has changed everything from the way our brains function to the way we socialize to how we understand “Truth.” In thinking about artist books in this light, I would like to look in particular at how the photobook as a genre of artist book reveals its influence by the non-linear hyperlink.

Whereas photo books since the nineteen-twenties have largely been single monographs, over the last decade, there has been an increase in photobooks which present a number of volumes in different formats in a container of some kind – a clam shell, a cardboard box, a slip cover, etc. The material consideration of the book formats in these photoboxes places them within the larger artist book tradition. More importantly, these book formats also reflect the influence of our experience of the world through the lateral movement of the hyperlink as opposed to the linear movement of the traditional single codex.

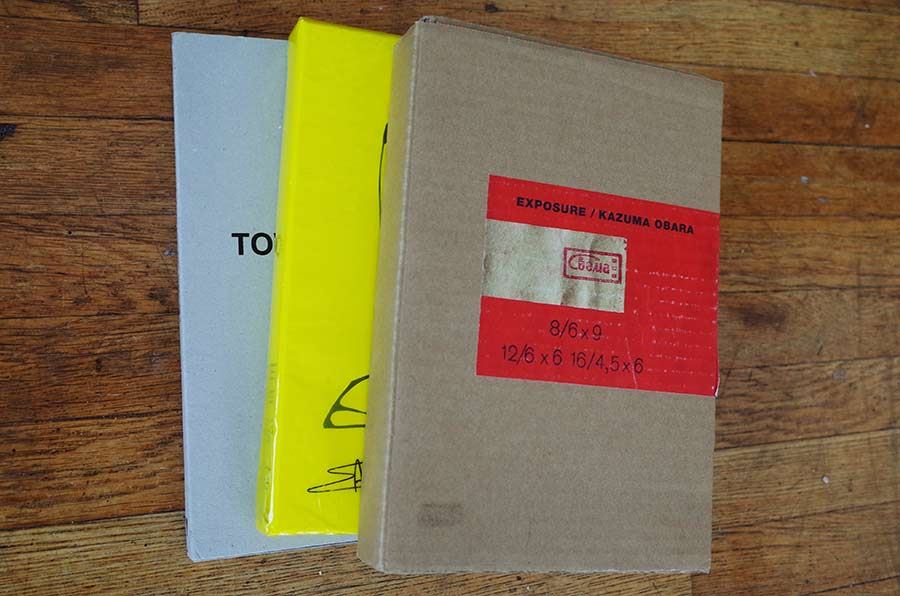

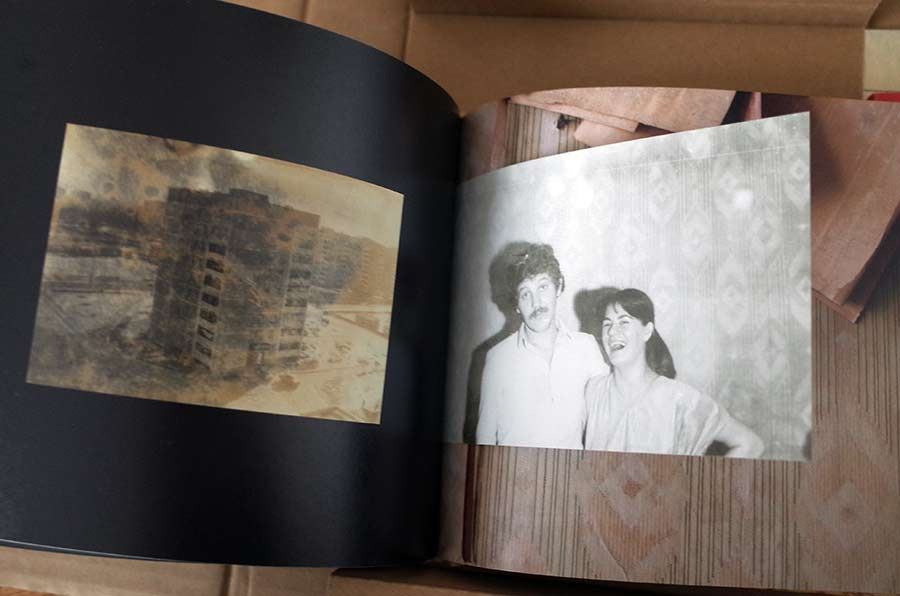

A fine example of an artist photobox is Kazamu Obara’s Exposure (2016). Exposure has as its focus Chernobyl and the box contains three formats – a soft cover, vertically formatted codex with text & images; a newsprint facsimile; and a horizontally oriented, hardcover photobook. Together, these formats provide three distinct perspectives: black & white found negatives with a reflective text; a historical reference; and a color view from inside a train and looking out as it transports workers to and fro from either side of Chernobyl. These 3 formats provide distinct perspectives that allow us to triangulate on the experience of this place: personal, historical, and documentary.

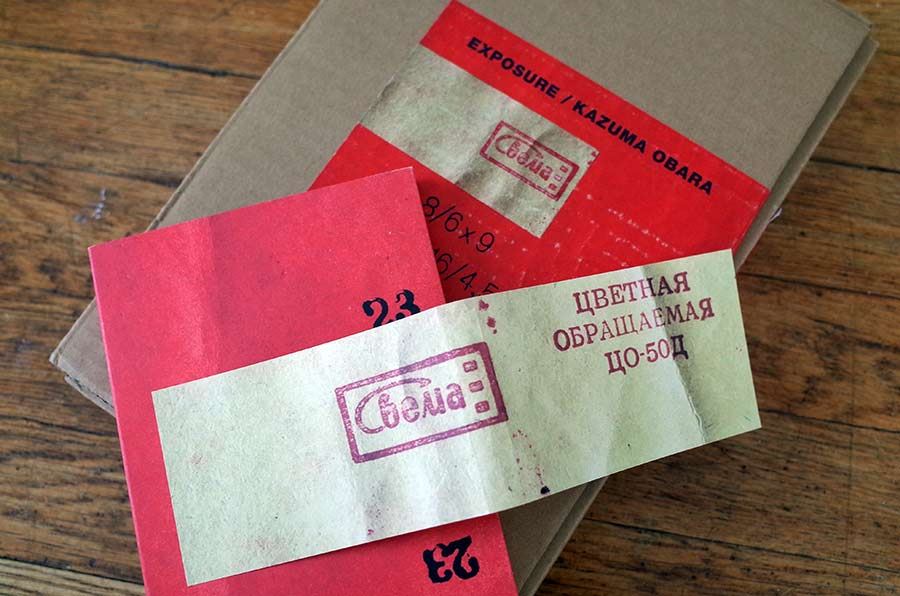

An additional layer of photographic content is the inclusion of film negatives set between a number of pages and facsimile 4x6 color photos tucked into others. These elements push the material attention further into the artist book realm. A finishing touch unifying the work includes a couple medium format film labels. They not only create the cover imagery for both the outside box and the b&w paperback book inside, but also they actually wrap around the box and the book inside, creating a seal (like the film wrap) that must be broken to open. This breaking of the seal can be interpreted in myriad ways.

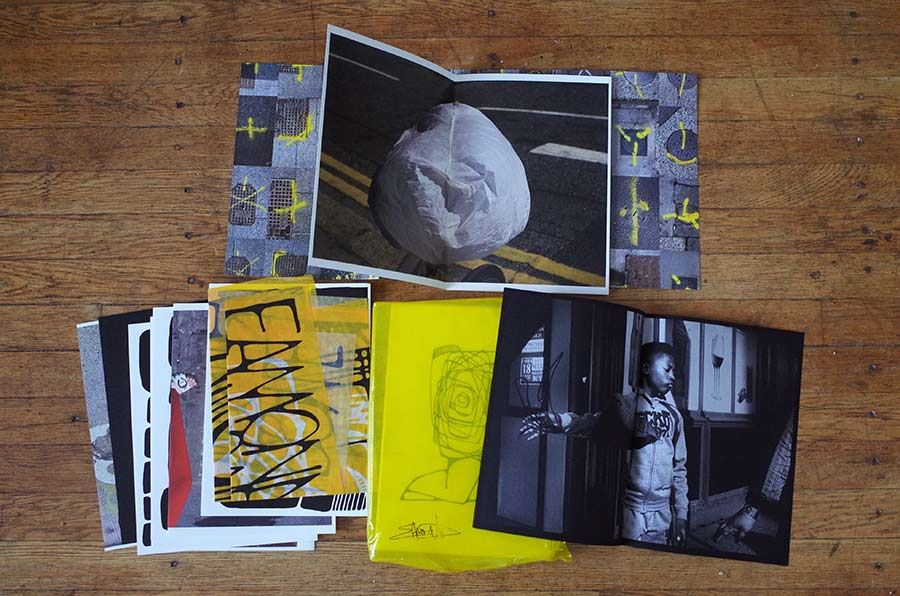

Another notable photoboox is End. by Eamonn Doyle, Niaill Sweeney and David Donohoe. This 13x8in hard slip-cover, wrapped in translucent, neon yellow glycine contains a handful of variously formatted booklets with different thicknesses of paper, printing styles, number of pages, and fold-outs. The cumulative effect of End. is more associative and is distinct from Exposure in that it is heavily design oriented. There is a strong abstract sensibility throughout, with exceptional bursts of clearly composed, though somewhat surrealist, color photos from Dublin. While not as precise or poignant in its details, End. nevertheless uses the multiplicity of formats to interrupt a particular viewpoint, thereby challenging, poking fun with, and disorienting our vantage point as readers.

To conclude, these photoboxes prove radical in terms of being broadly influenced by the hyperlink – represented by a diversity of perspectives that create a break from the modernist, single perspective, authoritative viewpoint. I leave as an open question whether this shift also reflects a change in the photographic community’s conception of “Truth” as it relates to the photographic medium.

[1] Multimedia: From Wagner to Virtual Reality, p. xxviii, ed. Ken Jordan, 2002, USA

Alexander Mouton has a background in film, literature, and photography. His artist books are self-published under the Unseen Press moniker, many of which are in collections internationally, including MoMA NYC and the Getty Research Institute, LA. Currently, Alexander is Associate Professor, Chair, Dep’t Art, Art History & Design, Seattle University.