The next few paragraphs will be dedicated to highlighting a small sampling of book arts environments within three universities or college libraries. In order to better understand the role the book arts play in each of these communities of higher education, I arranged conversations with the directors of each program.

The Book Arts Studio, University of Richmond, Boatwright Memorial Library, directed by Jen Thomas. [1]

UR students worked with Jen in the Book Arts Studio to develop creative writing strategies utilizing alternative book structures, which they taught to their partners at the Bon Air Juvenile Correctional Center.

The University of Richmond’s Book Arts Studio is a dynamic space that engages with students and faculty in course instructional sessions in addition to community engaged projects and initiatives, the latter being a truly remarkable aspect of Thomas’s work as director. The community engaged projects that Thomas organizes bring together not only students within UR but also the surrounding community, including local high school students. One such collaboration, titled The Spirit of Armstrong, pulled together 11 University of Richmond students with 21 high school students from Armstrong High School, a historically black high school, to document the voices of students and the community in which they live and learn through the creation of an editioned artist book. The creation of the edition resulting from the collaboration allowed students to explore personal narratives through the shared act of creation that is necessary when producing collaborative book works.

Members of an HIV support group worked closely with students in an American Studies Seminar to create book pages chronicling their journeys living with HIV. The books were bound with a Japanese stab binding and hung in an exhibition in The Valentine, a local history museum.

Other community collaborations have been arranged with the Bon Air Juvenile Correctional Center working alongside UR students in the First Year Seminar: Storytelling and Social Change to capture story and feeling as embedded within student created accordion books. Another of Thomas’s orchestrated projects worth mentioning is that which brought HIV community members and Richmond students together in order to tell stories of living with HIV through the creation of four collaborative cascading books.

The Library Book Arts Workshop, Dartmouth College, Baker Library, directed by Sarah Smith [2]

Students from a Spanish class learned to set type—touching their Spanish words—and printed a group broadside.

Sarah Smith’s work at Dartmouth College’s Library Book Arts Workshop focuses more heavily on the institutional community through course support and offering book arts workshops (open to both the college and local communities). In discussing the Library Book Arts Workshop with Smith, what stood out to me the most was the collaborations Smith puts together with faculty spanning multiple areas of study within the Dartmouth community. One of Smith’s stated goals is to work with as many areas and courses across Dartmouth’s campus as possible. There are many courses that engage through interdisciplinary collaborative work in the Library Book Arts Workshop at Dartmouth; 7 course instructional sessions/projects are planned for the winter of 2022. A few of those collaborations have involved environmental studies, Latin, English, and Native American Studies courses.

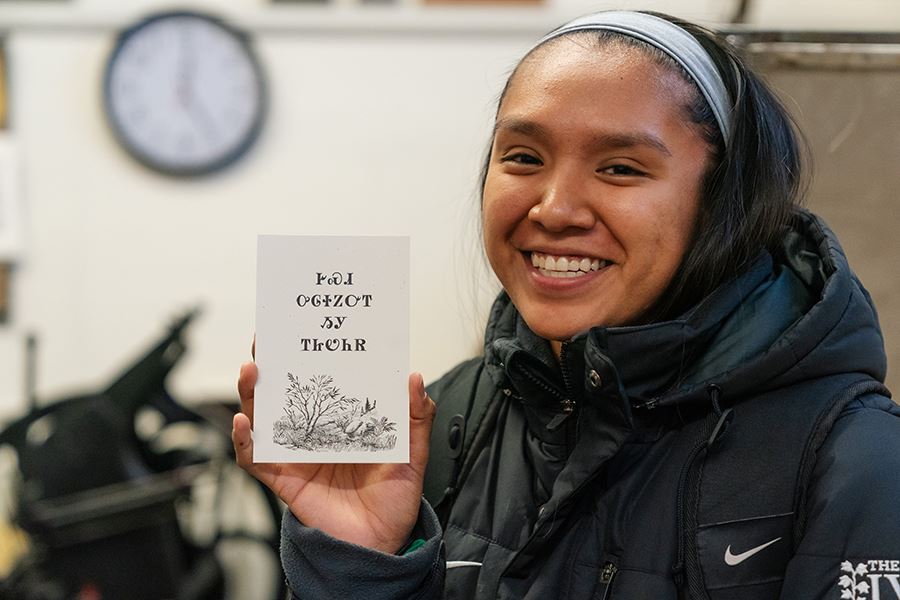

A student (Tia Yazzie, ’19, Navajo) from Native American Studies course, Pen & Ink Witchcraft holds up the postcard she just printed using the studio’s Cherokee syllabary type. The text is from Cherokee artist and poet Jeff Marley and it says, “Your words are not fleeting”.

One of these courses, ENGL 52.18, Netflix and the Victorian Serial Novel, provided an interesting opportunity for students to engage through the Library Book Arts Workshop during the lockdowns at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Students were able to explore the topic of seriality and its historic and contemporary implications on readership/viewership through the creation, production, and dissemination of serial pamphlets, created in collaboration with Smith and the Library Book Arts Workshop. The course HIST 96.08 Seminar: Pen and Ink Witchcraft: Native American History Through Treaties collaborated with the Library Book Arts Workshop to engage students through the tactile experience of printing Cherokee type, drawing meaningful and tangible connections to historic injustices through letterpress printing and written communication.

The Book Arts Lab, Wellesley College, Margaret Clapp Library, directed by Katherine Ruffin [3]

Students made paper in the Papermaking/Screen Print Studio at Wellesley College.

Differing slightly from the previous two book arts programs, the Book Arts Lab at Wellesley College hosts for-credit courses within the visual art and writing departments taught by BAL director Katherine Ruffin, typically 1 full class per term. These for-credit courses include ARTS 112 Introduction to Book Studies, ARTS 109 Two Dimensional Design, ARTS 222 Print Methods: Typography/Book Arts, and WRIT/ARTS 115 Word & Image Studio. Additionally, these courses are offered in conjunction with BAL instructional sessions for other academic courses. Much like the course support/instructional sessions offered by Smith at Dartmouth and Thomas at Richmond, in developing and facilitating instructional sessions Ruffin acts in a similar fashion to a librarian subject specialist, coordinating with faculty to build rich and meaningful content in support of course curricula. Ruffin and collaborating faculty use the BAL and library resources as jumping-off points for bringing disparate disciplines to form deep and meaningful enduring understandings through book arts driven content exploration. Each semester Ruffin will coordinate 10-15 instructional sessions per semester.

A faculty workshop being hosted in the Book Arts Lab.

The juxtaposition of book arts studio environments to library stacks, special collections, and archival material (not to mention maker spaces) has the potential to build and support information literacy, promote learning, and provide entry points to information in ways that may not have been previously supported by traditional library settings. Ruffin points out that the BAL’s proximity to special collections, archives, and other library resources creates unique creative synergies that encompass both historical and contemporary research.

An additional facet of Wellesley’s BAL worth mentioning is that it is also home to Annis Press, a literary and fine art press originally began in the late 1940s under the imprint of Red Bud Press. While not overly active, Annis Press on occasion will produce work with students, faculty, and visiting writers and artists such as Kiki Smith, Toxicology, 2009. [4]

Bibliography

[1] Clark, Kyle, and Jen Thomas. Book arts in college and university libraries. December 16, 2021. Personal interview conducted over Zoom.

[2] Clark, Kyle, and Sarah Smith. Book arts in college and university libraries. January 5, 2022. Personal interview conducted over Zoom.

[3] Clark, Kyle, and Katherine Ruffin. Book arts in college and university libraries. January 7, 2022. Personal interview conducted over Zoom.

[4] Smith, Kiki. Toxicology (letterpress and relief printing), Annis Press, 2009, Whitney Museum of American Art, https://whitney.org/collection/works/36104.

Kyle Anthony Clark is an artist and educator living in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Kyle works at the University of Michigan Library’s conservation laboratory and as an instructor in the Book Arts Studio. Kyle maintains an independent practice and teaches courses and workshops on artists books, bookbinding, letterpress, and papermaking.