Ancient examples of accordion-folded books have been found in many parts of Asia, including China, Japan, Korea, Thailand, India, and Burma. In China the accordion (musical instrument) is called a shou feng qin, which literally means “hand-wind-instrument.” The name for the book structure is jingzhe zhuang: jingzhe means “neat-folded paper” and zhuang means “binding.” The earliest examples of jingzhe zhuang bindings are from the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). There were two earlier systems in China for “binding” texts. Some texts were written on silk cloth, usually rolled up as scrolls. The Chinese word for this structure is shoujuan, which literally means “hand roll-up.” Texts were also written on wood, usually bamboo cut into thin vertical strips, laced or knotted together horizontally with cord, then either rolled like a scroll or folded back and forth in a stack. The folded variation of this binding style is known as jian du, and examples date back to the fifth century BCE. It was not until after the invention of paper, in the second century CE, that Chinese bookmakers adapted the jian du structure to make jingzhezhuang bindings. A miniature jingzhe zhuang (10 x 14 cm) was found at the Dunhuang archaeological site in Western China, and thus, made before 900 CE, it is the oldest-known miniature accordion book.

In Japan, the accordion-folded book structure is called an orihon. The word combines the root words ori (fold) and hon(book). According to legend, it was during the Heian period (794–1185 CE) that a Buddhist monk squashed his sutra scroll and then folded it up, thus inventing the orihon binding. Japanese orihon books were made using paper: either a single long strip folded back and forth, or several smaller strips connected together before folding. Another variation of the orihon binding was called a sempuyo. In this binding, individual folded sheets are arranged with the folds all facing the same direction, and then each fore edge is adhered to the adjacent fore edge. The cover is adhered to the first and last pages of the text block, but it is not attached to the spine. Because of this, the sempuyo is often called a flutter book: if it is dropped or blown by the wind, the pages will flutter but remain attached to the covers. It is said that monks used such books medicinally, believing that the breeze created by moving the pages of the holy sutras could heal an injury.

In pre-Columbian Mexico and Central America, the Aztec and Maya made books with folded structures. These books are commonly called códices. Mayan códices were written in hieroglyphic characters, called glyphs, on amate, a paper-like material made from the bark of a certain type of fig tree. There was a Mayan glyph for the word códice, juun, but it looks more like a hamburger than a book. Written pages were pasted together and then folded back and forth to create an accordion-folded book. The Spanish invaders destroyed most of the original códices, and though some original text blocks survived, there are no original bindings. Some scholars believe the text block was glued to wooden covers, others that the text block and covers were wrapped together with leather cords.

It is unknown when the first accordion book was made in Western Europe. The oldest extant example I could find was handwritten, in Cyrillic script, in 1330. This manuscript, known as Canones et carmina sacra quae…, is now in the Netherlands’ Leiden University Library.

While there were other examples of accordion-folded manuscripts, the binding structure was not used in the early printed books. Although there were over 30,000 distinct editions printed during the incunabula period (1450–1500 CE), no known incunabulum has an accordion structure.

Other than the Canones et carmina, the earliest accordion books made in Western Europe that I have discovered were miniature books printed and bound to be sold as souvenirs. As far as I know, none of those books include a printed date of publication, but some have the publisher’s name (for example, the Recollections of . . . series printed in London by J. Newman & Co.) and others have a traceable provenance, so we know they were made in the early to mid-1800s.

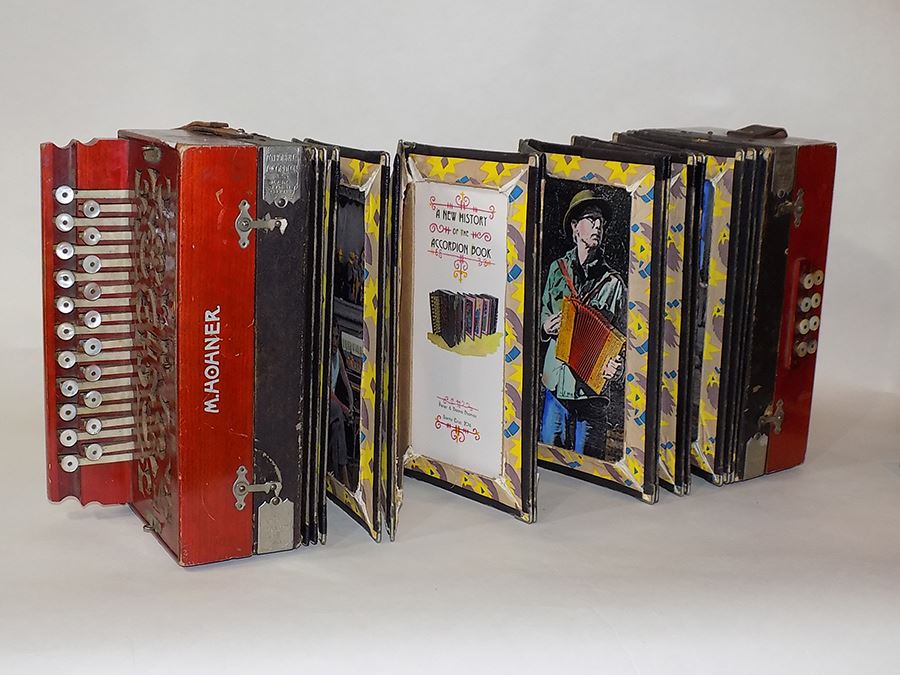

We may never know who made the first accordion book, or when it was made, but at least we do know when and who made the first real accordion book. Accordioning to respected book arts historians: in 2002 Peter and Donna Thomas cut the bellows of an accordion, allowing them fold back and forth, inserted paper panels printed with text and image into the folds, and made their first Real Accordion Book out of Peter’s old 12 bass piano accordion. That first real accordion book was followed by a series of others.

Peter and Donna Thomas. A New History of the Accordion Book. 2016.

The works are tied together by structure, text, and image. A collection of photographs rotates through the series – old favorites reappearing, new images being presented for the first time. The texts have, for the most part, been explorations into the history of the accordion and of the accordion book. We have tried to add new information to each subsequent book, and since a history of the accordion book has not been previously published, finding information has been hard. We hope that by sharing what we have learned in these blog posts, others will come forward with what they have discovered, and together, as a community, we can write a more complete history of the accordion book.

Peter and Donna Thomas are book artists who make editioned and one-of-a-kind books. They make the paper, print, illustrate, and bind their books, combining the precision of the fine press aesthetic with the creativity found in contemporary artists' books. Between 2009-2019 they traveled the USA as the Wandering Book Artists.