Wonder is underrated today, even dismissed, relegated to sensational headlines in glossy magazines or social media drama—in other words, treated as irrelevant or hyperbole. But wonder, defined as “a feeling of surprise mingled with admiration, caused by something beautiful, unexpected, unfamiliar, or inexplicable,” can be a powerful strategy for an artist, and particularly for an artist wishing to entice and involve a viewer.

In their 2001 book Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750, Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park trace the shifting status of the state of wonder through history. In the preface, the authors stake out their different perceptions of wonder: “One of us believes that wonders appeal because they contradict and destabilize; the other, because they round out the order of the world.”[1] It is in the meeting of those two responses—to disrupt and then reclaim—that wonder exerts its power, which can be especially useful to artists who make work about difficult truths.

Wonder is on show in the exhibition Reclamation: Artists’ Books on the Environment, which arose in response to a global call to action. Peter Koch and others called for artists to “raise a ruckus” in 2021, to educate and demand change around environmental threat and loss. Jeff Thomas, Executive Director of San Francisco Center for the Book, agreed to host the show and publish an illustrated catalogue with essays. Thanks to another prompt from Koch, San Francisco Public Library signed on as a second showing site. [2] I was invited to write two blog posts, as co-curator of Reclamation with Jeff Thomas, and as one of the show’s three jurors and catalog essayists (joined by Mark Dimunation of the Library of Congress, and Ruth Rogers of Wellesley College). As jurors, in addition to prioritizing works of excellence and compelling content, we sought works that would reach across the chasm of anxiety and disbelief that many subconsciously employ to distance themselves from unsettling and threatening content.

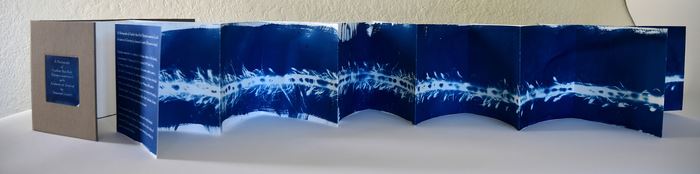

Wonder bridges that gap. For example, Judith Tentor’s accordion book, A Photograph of Feather Boa Kelp (above), draws attention from its deep blue cyanotype contact print. A cyanotype is activated when an object is laid atop photosensitive paper, allowing the action of light to create a negative silhouette when the object is removed. Feather Boa Kelp’s initial impact is in its scale of nearly fifteen feet, an accomplishment in the cyanotype medium. Equally striking is the work’s lacy patterning that ripples along the folded sheet as if the kelp (a subgroup of seaweed) is still afloat. Once a viewer advances into reading proximity, the text reveals that its openwork pattern is evidence of the feeding of a seaweed limpet, which has followed the kelp in its expanding range due to the warming ocean. Tentor’s specimen was found in the waters off San Diego, and the kelp’s range now reaches from Alaska to Mexico. As an artist’s book, Feather Boa Kelp carries evidence of climate change directly into a reader’s hands.

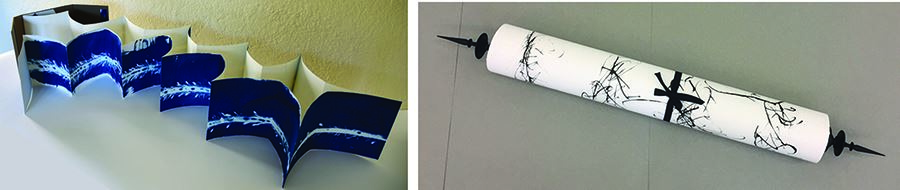

A second work, Ten Meters of Mycelium by Lizzie Brewer (above), also draws a viewer’s gaze through the beauty of its ink and graphite drawings of mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, depicted here in fine white filaments that gather and release across the sheet. The title also notes the scroll’s extraordinary length of ten meters (thirty-three feet), the majority of which remains hidden, furled within the scroll structure, viewable only in increments. Wondrous indeed, a viewer can imagine slowly exploring the sheer breadth of it, as the exquisite renderings come into view only to be tucked away again as the scroll is forwarded. Like a microscopic sample brought into focus, Brewer’s drawings of magnified mycelia represent billions of fungi, mycelia, and roots. This life-giving network produces and nurtures the soil’s biosphere across the earth’s surface—literally sustaining the ground under our feet.

Through wonder, A Photograph of Feather Boa Kelp and Ten Meters of Mycelium transform our familiar but unnoticed forays into a heightened mindfulness of the urgency of climate change, while exploring a shoreline or simply walking on terra firma.

[1] Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park, Wonder and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750 (New York: Zone Books, 1998) 11.

[2] Reclamation: Artists’ Books on the Environment is on show at San Francisco Center for the Book from June 9 – September 26, and at San Francisco Public Library from June 19 – September 5. I also wish to thank Jennie Hinchcliff of San Francisco Center for the Book, and Joan Jasper of San Francisco Public Library, for their dedication throughout this project.

Betty Bright is an independent writer, curator and historian who helped to start Minnesota Center for Book Arts (MCBA). In 2005 she published No Longer Innocent: Book Art in America 1960-1980, and continues to write and curate, including contributing to the forthcoming Materialia Lumina (Stanford University and The CODEX Foundation, 2021).