Intentionally bad typography: this meme has been circulating for at least six years.

"Authenticity" is one of the topics in my Critique Workshop. We see many works of book art that are made by people with a lack of training or experience, but with a lot to say. As educators we see lots of that. Some of the most powerful work I've seen was made by inner city teens in a series of Center for Book Arts (CBA) summer workshops titled Cultural Autobiography, conducted by Cheryl Shackleton Hawkins 1993-2000.

Work by Antonia Pocock for the exhibition Student Work and Cultural Autobiography. Center for Book Arts, Sept. 1 to Oct. 31, 2000.

Sometimes we see works that are done by highly skilled practitioners in a style that appears to be untrained. Is it simply fake outsider art, or does the intent of the creator play an important role in critical evaluation? Is it important that the viewer knows what the creator was trying to achieve? Does the medium in which it appears make a difference? Does it matter if the target audience is Artworld insiders or the general public?

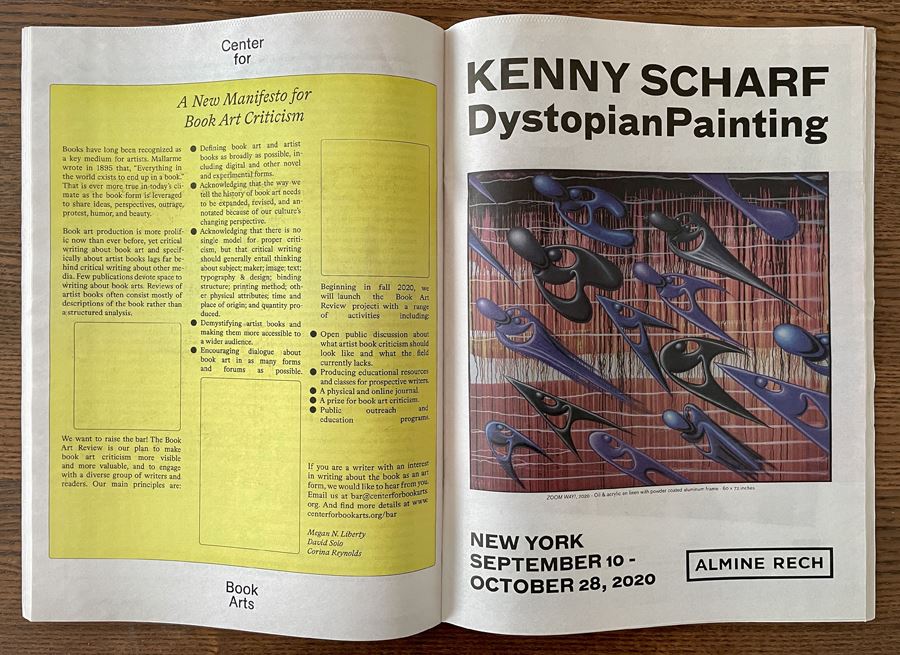

This issue arose close to home last September, when CBA published "A New Manifesto for Book Art Criticism" as a full page ad in The Brooklyn Rail, as a web page, and as a PDF.

When I first saw it I sent an email to CBA asking if was done by a volunteer or a student, noting the inconsistent line spacing, justification, and other typographic issues. A reply came quickly:

"This design was created by knowledgeable, professional designers who are highly regarded in their field. And from a contemporary design perspective it is right on point. The word spacing, hyphenation, and box outlines are all conceptually related to the content of the manifesto and the history of artist’s book criticism."

I was confused and mystified. What is the conceptual relationship of ugly typography that is hard to read to a manifesto advocating criticism of typography and design? Was that the point? Was this meant to be criticized? Or to be seen by a specific audience? Was it a joke? I've read some artist book criticism, and written some, as well as conducting Critique Workshops for four decades. I needed to ask for advice from those who know more about typography, so I wrote to a few typographers, including the designers of the manifesto. Robert Bringhurst, author of The Elements of Typographic Style, was the first to respond:

"Professionalism has its pitfalls as well as its benefits. You of all people will recall the distinguished economist Arthur Okun’s observation that 'anyone except an economist knows without asking why money shouldn’t buy some things.' I fear it’s also true, in the present climate, that anyone except a 'cutting-edge typographer' knows lazy and incompetent typography when they see it.

"I was delighted to read that the CBA plans a new periodical, the Book Art Review. But its 'New Manifesto for Book Art Criticism' delivers a self-contradictory message because it’s incompetently composed.

"Four of the fifteen paragraphs in the manifesto are set with the 'block justification' switch turned on. This forces the last line of a paragraph to fill out to full measure, at the cost of outlandish word spacing in all lines from first to last. This is what you see in the bottom paragraph of the first and second column, the top paragraph of the third column, and the final bulleted paragraph, farther along in the third column. First-week design students often make mistakes like this. Anyone who charges money for doing typography, or who undertakes to teach the craft, ought to laugh at such errors, or scowl, as their temperament permits. But to defend such an error is blatant self-incrimination.

"The justification and word-spacing in the other eleven paragraphs of the manifesto is also pretty lousy, and this is because the typesetter failed to set the justification parameters to reasonable values. Tuning a justification engine is slightly more complicated than just turning a switch on or off, so I don’t expect typography students to learn it until the second week of instruction. If they don’t have it down by the third week, I will start dropping hints that they should consider a different profession.

"Those are the two most obvious problems with the design and execution of the manifesto. It would also help if the authors could spell the name of the poet Stéphane Mallarmé – the only authority they quote. And it would help if the text were set using text figures (old-style figures) rather than lining figures. Lining figures belong in classified ads. They do not belong in books nor in any discussion of book arts, nor in a proposal for a book arts periodical.

"Incompetence per se is not hard to repair, and institutions like the Center for Book Arts were created for just that purpose: to teach those who are willing to learn. Proud and defiant incompetence is something else again. Those who broadcast their ignorance and insist they have nothing to learn (like a certain American president I can think of) are a menace to their fellow citizens.

"The claim that the design of this manifesto 'was created by knowledgeable, professional designers who are highly regarded in their field' and that 'the word spacing, hyphenation, and box outlines are all conceptually related to the content of the manifesto and the history of artist’s book criticism' is just pretentious nonsense. The setting is incompetent, and anyone whose eyes are not stitched shut can see that this is so."

Next I heard from Ellen Lupton, Design Chair at MICA and Senior Curator, Contemporary Design at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum:

"Whether the effect successfully communicates its own confidence is a matter of opinion. This design is an example of what is sometimes called 'default modernism.' Just because the designers know what they are doing doesn't mean that readers necessarily get the joke."

Wael Morcos, Partner at Morcos Key, wrote:

"It’s part of a design movement self-dubbed “critical graphic design” using graphic design as methodology for research into other disciplines like politics, sociology, sustainability… Sometimes the formal interpretation is surprising and detached from the needs of a corporate client. Sometimes it’s just another affectation, an attitude, a trend. I personally don’t buy the argument that if it’s rigorous thought, it has to be unpleasant to look at or deliberately confusing."

The final word came from the manifesto's designers, Jas Stefanski and Lauren Thorson of Studio—Set, who also designed the new CBA Website and this spiffy animated Instagram post for the Center's annual benefit, which takes place May 11. They clarified the objective:

"In regards to your question, it was not intended to be a joke nor look like outsider typography. The typography emphasizes the immediacy inherent to newspapers, mass produced/circulated printed formats, etc."

After reading the replies to my query I had a better understanding of why I was confused, and an appreciation of how difficult it can be to communicate an idea typographically when readers come to the page with many different perspectives.

Minsky is a book artist, curator, and historian. Founder of Center for Book Arts, Incorporated 1974, the first organization of its kind. He serves on the CBAA Book Art Theory subcommittee. The Richard Minsky Archive is at Yale.