Dennis J Bernstein and Warren Lehrer have had successful collaborations in the past, best known, at least among book artists, for their extraordinary artist book French Fries, which looks and projects itself as public theatrical performance. Most recently, they are the creators of Five Oceans in a Teaspoon, which similarly sits at an intersection of forms—poetry, visual text, and performance—but in this case performance is private.

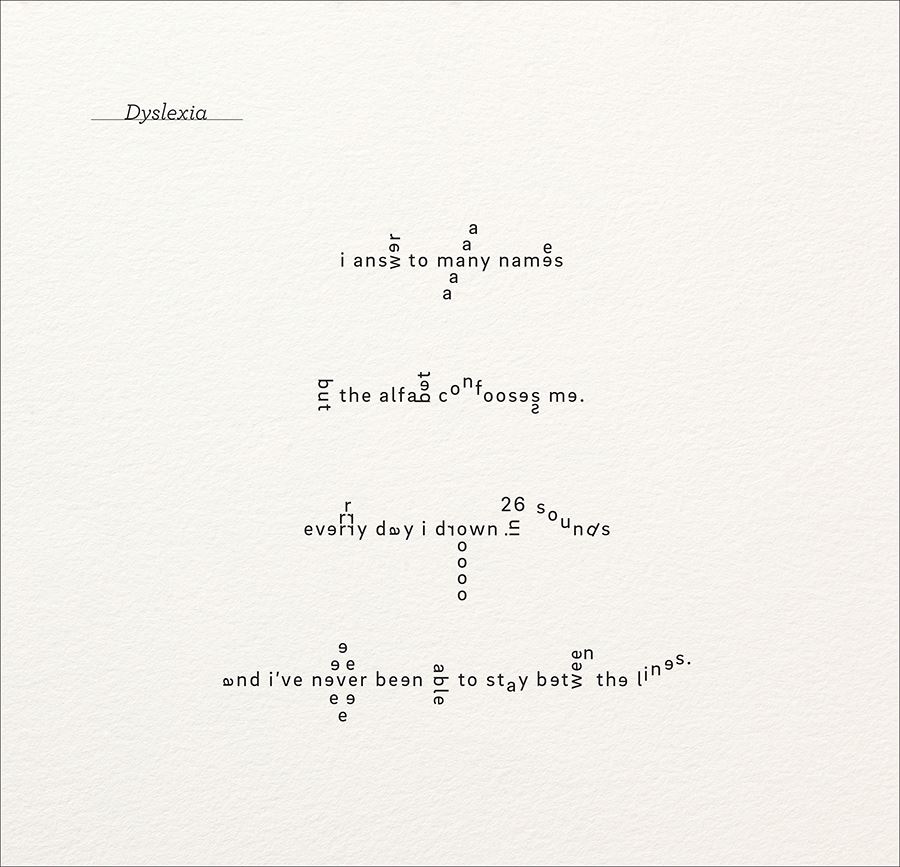

The poems—informal, elliptical, moving, often having a quirky, humorous undertone—were written by Bernstein, many appearing in various publications; Lehrer, responding to the forms beneath the poems, turned them into what is typically called concrete poetry. His visualizations involve performance as much as visual composition. That in part comes from one’s sense of hearing the voice of the speaker, his intonations, the aural equivalent of punctuation or no punctuation, the rise and fall of cadences. But it is also the result of the reader’s being thrust into a time-based experience (private rather than public), more aware than usual of the act of reading. We are as conscious of that as we were when we first learned how to read. Perhaps that in itself adds to our sense of discovery and pleasure when we finish any one of the poems from this collection. But the very act of conscious reading enacts what is essential to each poem’s emotional and metaphoric center. In, for example, the first poem, “Dyslexia,” letters appear above and below lines, repeated, irregularly placed, in a way that forces the reader to slow down and, like a dog with the proverbial bone, to worry a word.

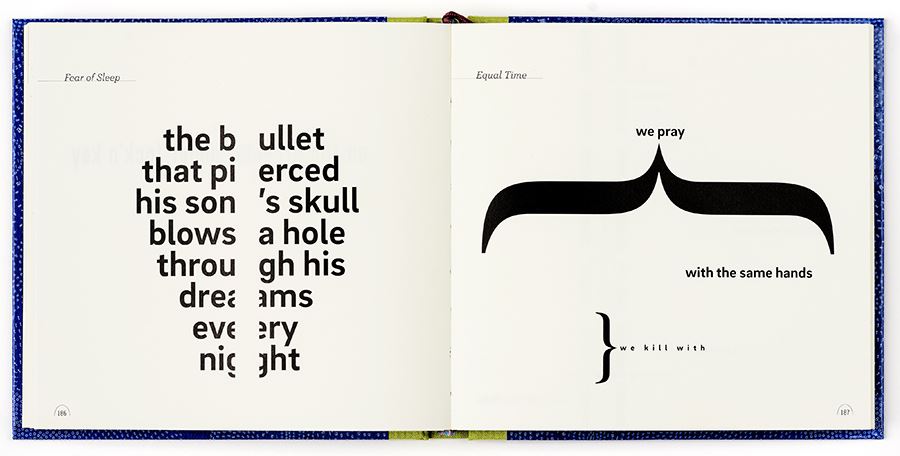

Lehrer at times includes minimal images—lines, boxes, black spaces, shapes, patterns—which function as part of the graphic vocabulary, but text is the primary image in these poems. There is no grid controlling placement. Lines and words and letters can appear anywhere, in any direction, in any shape. Poems can end in periods, in dashes, or in nothing at all, undercutting the ending itself. And the spaces among and between the elements of the text similarly play meaningful havoc with the page.

The visualizations are a tour de force, but, more important, they enact the poems themselves, revealing their poignance and complex humanity. The subjects cover much of a life, beginning with childhood and ending with death, in particular, that of the writer’s mother and father. They also include poems about other lives, people the writer has connected with—including, but not limited to, people in prison, the front lines of war, poverty, street violence.

At least in the last century, poetry, in particular free verse, has closer ties to the visual arts than other forms of literature in that space and the arrangement of lines can be as important as the words themselves. Poetry also has closer ties to the oral, to music, than other literature in its musicality, in the importance of rhythm, and the way sound molds meaning. Connected to both is a reading process as a private performance. That makes Bernstein and Lehrer’s Five Oceans in a Teaspoon a rather remarkable introduction to poetry itself.

Coda:

I sent the above piece to Warren Lehrer, who suggested that I add a link to an animation of one of the poems. I admitted I had been resistant to looking at the animation and asked him how he would compare the experience of reading/seeing the page and screen versions.

Warren Lehrer's response:

I too am interested in that comparison and space between reading a poem on the page and watching the video, and how the two experiences speak to and inform the other. Normally you’d think that reading on the page is a more active experience, and watching a video or film is more passive. But in making the animations I was interested in splitting the difference between active reading and watching a performance.

For instance, the printed poem Avowel (p. 34) presents itself at first as a puzzle or like a math equation of some kind. It requires “conscious reading” (as you put it) on the part of the reader—to piece together what the words are and think about the meaning and double meaning(s). On the one hand the poem is about the small minority of vowels (in the English language) calling the shots over the consonants. It’s also about the domination of a more powerful group over a population with less power. I believe the animation requires the same kind of active participation/decoding by the reader. The animation also allows me to extend and evoke the metaphor of the vowels in the poem being increasingly pronounced and isolated from the consonants which hang and swing from the vowels as if from ropes or at least like puppets on strings (which, in the U.S. context, could conjure images of the Jim Crow South, or in a global context—any minority segregated and subjugated by a majority). Original soundtracks (composed by Andrew Griffin) also contribute to the experience, as does the possibility of an engaged reader going back and forth between page and screen.

“Avowel,” one of ten animated poems from Five Oceans in a Teaspoon.

Susan Viguers is a book artist, whose books are in numerous public collections. She was Director of the University of the Arts’ MFA Book Arts/Printmaking program for nine years. She has a Ph.D. in English and has published scholarship extensively. Her most recent award was a Rockefeller Bellagio Arts Residency.