On page one, Michelle Ray’s book The Cave Protection Act of 2013 defines the cave as “[a]n empty space, void, receptacle, musty smelling and awaiting deposit of trash or carcass; hiding space for weapons, unsent love letters; glory hole; home to…animals obliged to live underground.” The book concerns the decades-burning underground anthracite coal mine fire in Centralia, PA.While a plethora of popular media have addressed the fire and relocation of most of the borough’s residents (including a This American Life podcast and a feature-length documentary), Ray’s work slips genre to engage the calamity and peculiarity of the Centralia fire via language, form, materiality, production method, and typography.

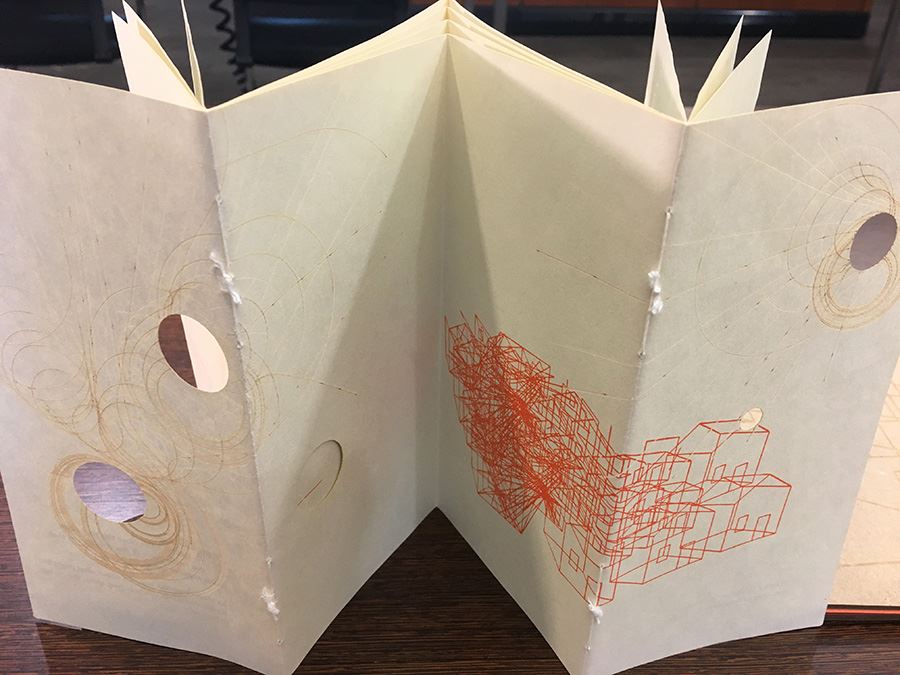

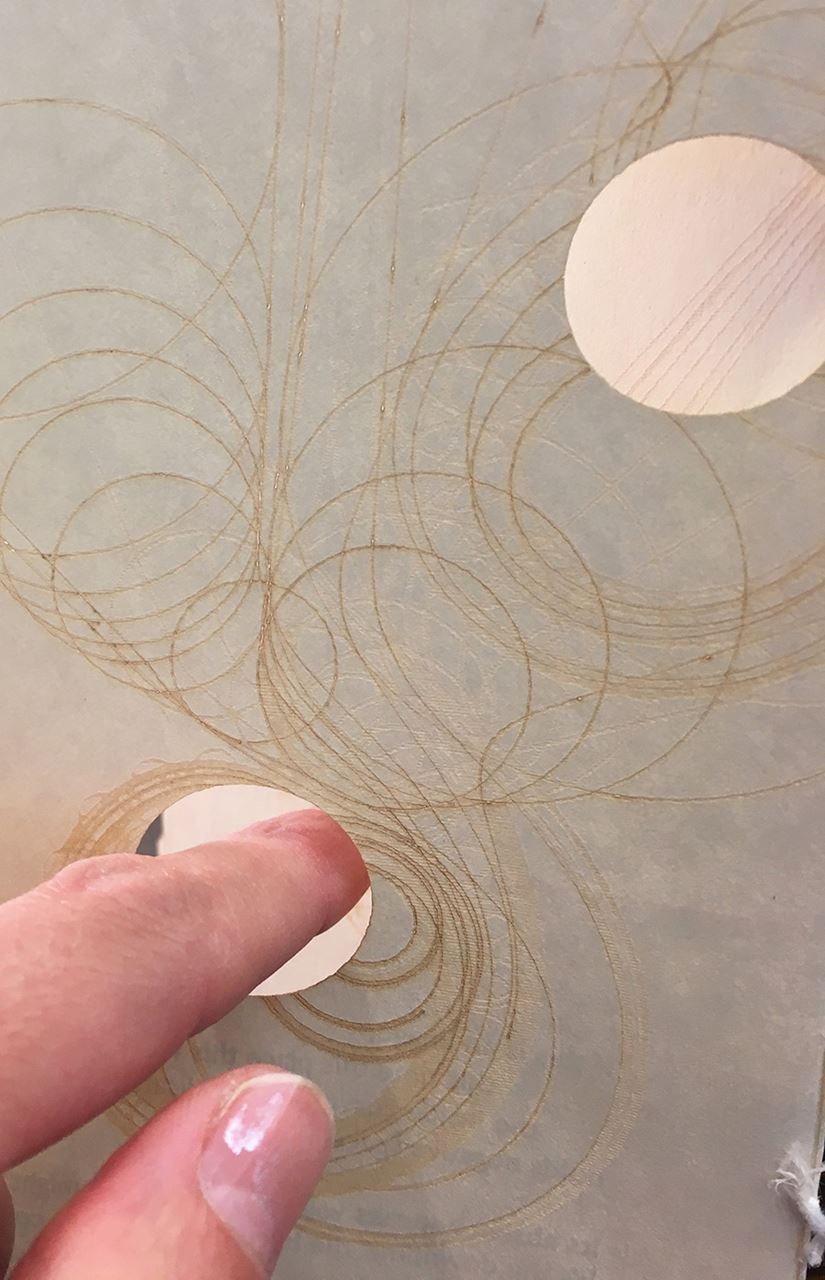

The book’s simple structural design generates a surprisingly complex object. Four accordions of varying panel width are stacked then sewn through two opposing valleys, creating a layered V-shape in the center flanked by four pages on either side. Each page is successively wider than the next, which adds to the layered effect. The form speaks immediately to its subject; the reader peers into the curious formation of the folded depths as into a miniature cave. Holes in the pages lend additional perspective complexity and affect the movement of light and shadow through the textblock.

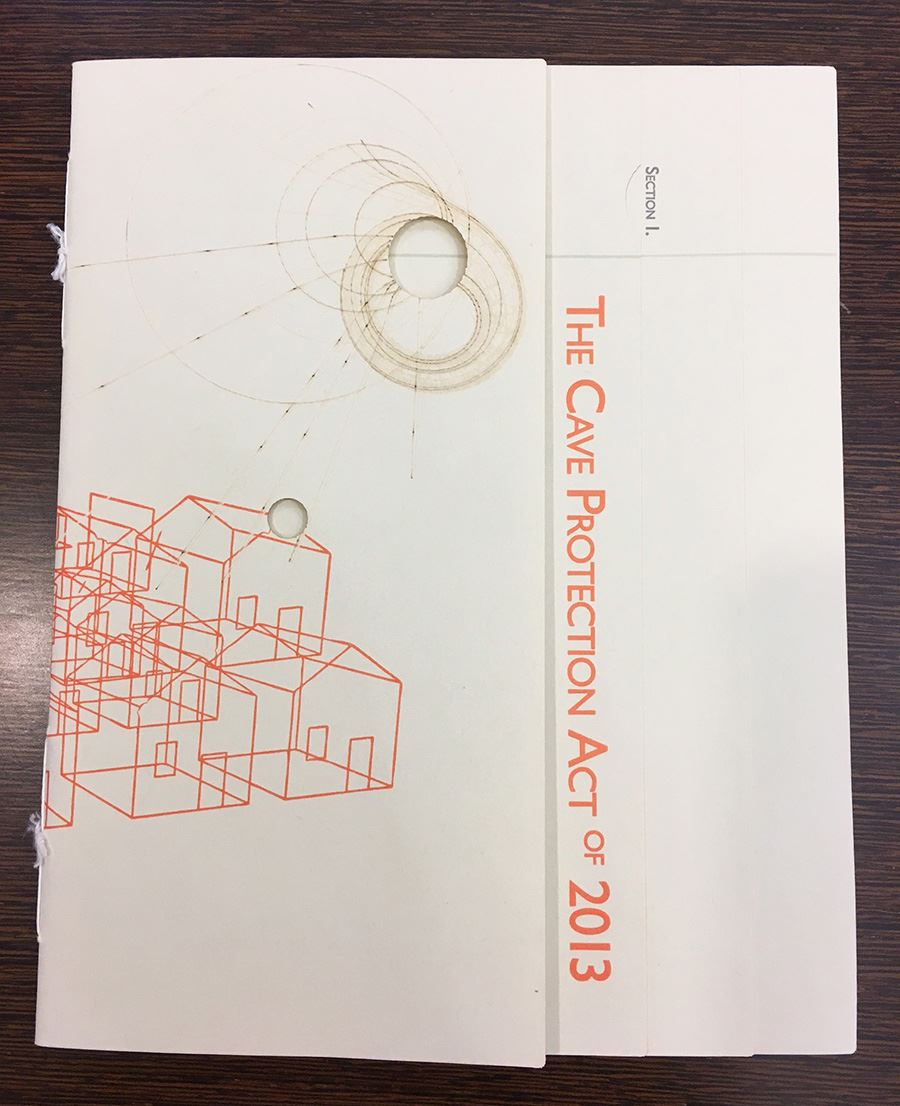

Printed on a neutral, machine-made paper, The Cave Protection Act bears some resemblance to a government document. The tiered pages allow for semicircular thumb tabs to indicate sections. Closed, it resembles a pile of papers atop an institutional desk. But the trappings of officialdom are gestures, rather than an overarching conceit—pointing to the role of governmental agencies—broadly with regards to land protection and more specifically to events in Centralia—from the beginnings of the fire in a mine-pit-turned-landfill to the declaration of eminent domain that relocated its residents.

The layout supports two textual modes. The first part, in landscape format, presents the language of the titular “Act,” which might be described as poetic legalese. The Act is broken into numbered sections and lettered subsections. Pale green text in a larger point size floats on two pages, offering speluncean didacticisms: “The cave should pose a question, rather than an answer,” and, “There needs to be room in the cave for contemplation.”

The second part, in portrait format, has a lyrical voice, loose poetic structure, and reduced ironic distance. The alternating orientation requires constant rotation of the book literally to consider the problem from multiple perspectives.The divisions between parts, however, are porous (like the textblock and the ground in Centralia); the intimate voice of part two seeps into the bureaucratic language of part one; for example, from section 2A, “No person shall be held liable for injuries. The older I get, the closer the acts of laughing and crying become.”

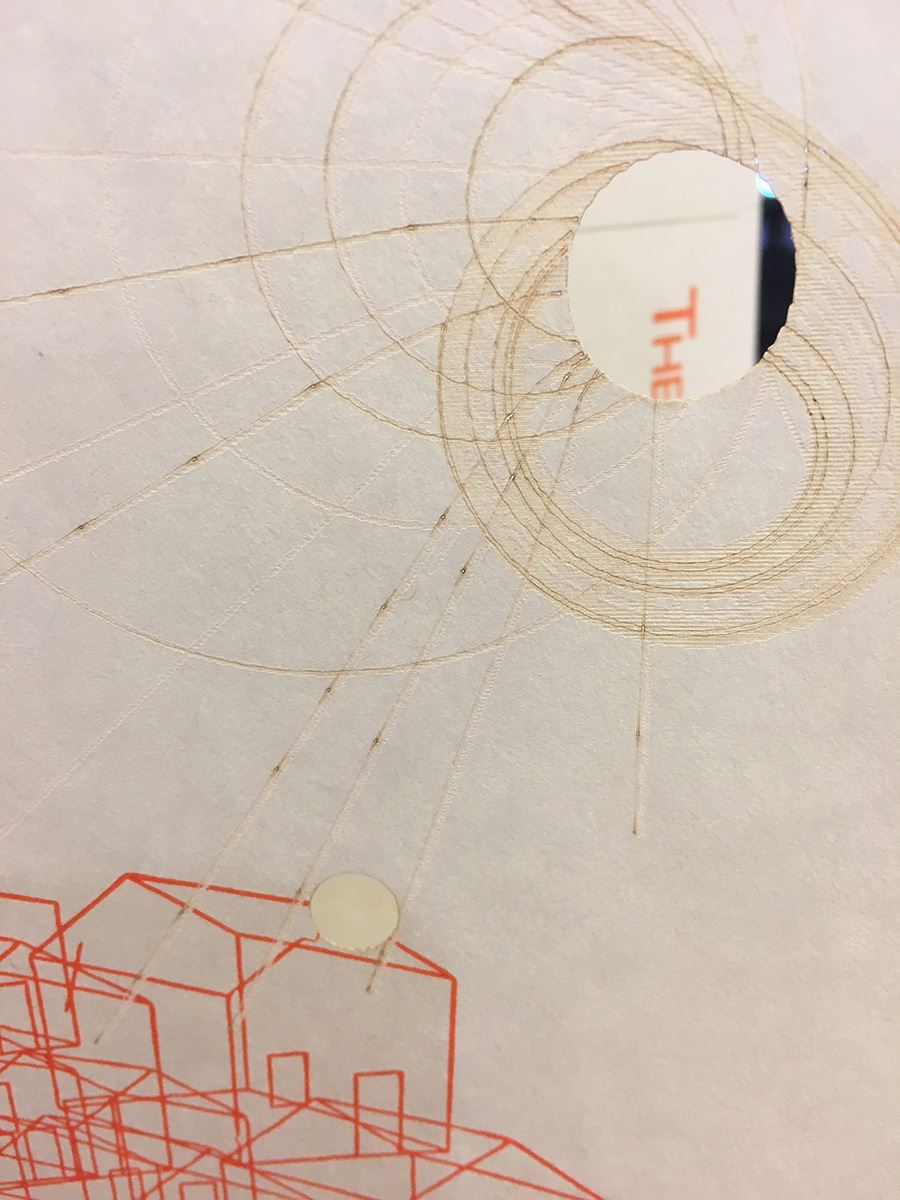

Ray’s production methods also engage her concepts. Laser engraving leaves a trace via the removal of material, visually supporting the idea that “there is meaning and identity to be found in natural erasure” (sec. 1A). Laser cutting leaves a signature burn; in this case the laser is both an efficient tool and a reference to the fire burning underground.

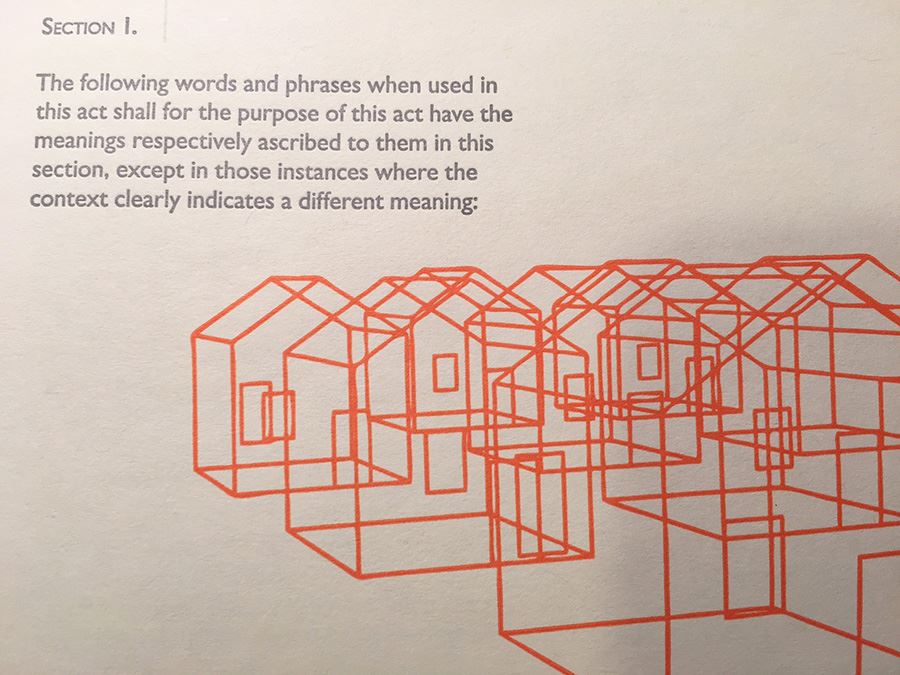

The imagery was created using 3D imaging software. Its technical acuity and fineness of detail resemble an architect’s plan. Laser-etched circles and lines radiate as abstract diagrams. Line drawings of identical houses interact—scattered and sparse, then crowded and overlapping. The forms are skeletal, non-specific representations, whose meaning changes based on their relationships to other house forms.

Section 1C reads, “Identity starts with the home. A home will remind you of who you are, ground you in your you-ness. Place is her anchor. In the absence of a physical home, would-be dwellers begin to ask the real questions of their place.” This speaks to the impact of the underground fire on community in the literal quagmire of Centralia. Simply structured and thoughtfully designed and produced, The Cave Protection Act quietly “poses question[s], rather than…answer[s].” It doesn’t explain the origin or the science of the fire; the methods tried and money spent fighting it; nor does it retell the narrative of the political turmoil and conflict among and surrounding the community. It subtly alludes to Centralia and the strangeness of a particular environmental reality precipitated by human land use amid a broader exploration of home, community, absence, and presence.

This blog post is adapted from a paper presented at the twelfth biennial conference of the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment.

Photos taken by the author in the Rare Book Department of Special Collections at the University of Utah’s J. Willard Marriott Library.

Emily Tipps is Program Manager and Assistant Librarian (Lecturer) at the Book Arts Program at the University of Utah, and the proprietor of High5 Press.