Where strictly textual books must always grapple with the challenges of conveying meaning through abstract signs, the multi-faceted artist’s book can employ the visual, tactile, and inter-mediated to engage its concepts. Artists’ books—through engagement with materials, structure, production, scale, action, text, texture, color, and image—are well positioned to participate in environmental narratives and dialogs. As (typically) sequential, book forms are ideal to render or interpret environmental change. Lin Charlston’s 2011 book Fragment by Fragment: Signs of the Peat Bog Disperse into the Wind navigates a particular instance of environmental destruction using unique visual-textual methods.

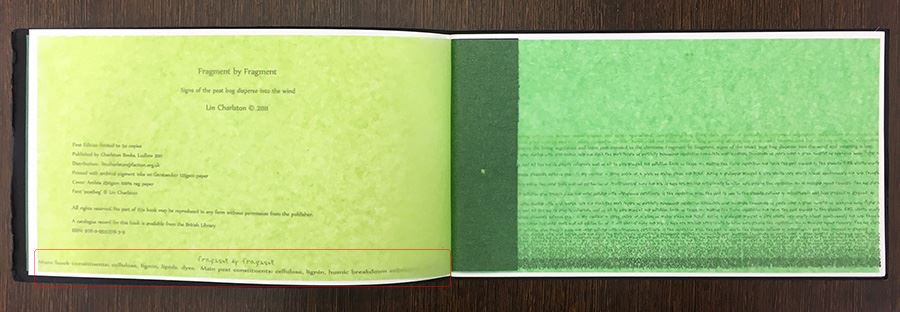

Fragment was shown in an exhibition “in which six artists responded to a damaged peat bog in the Black Mountains of Wales.” The book acknowledges its materiality immediately: “Main book constituents: cellulose, lignin, lipids, dyes. Main peat constituents: cellulose, lignen, humic breakdown substances, lipids.” Here, Charlston effectively asserts that the book and bog are materially analogous. Notably, the book does not wait to deliver concept; this assertion appears in the front matter alongside the standard bibliographic information.

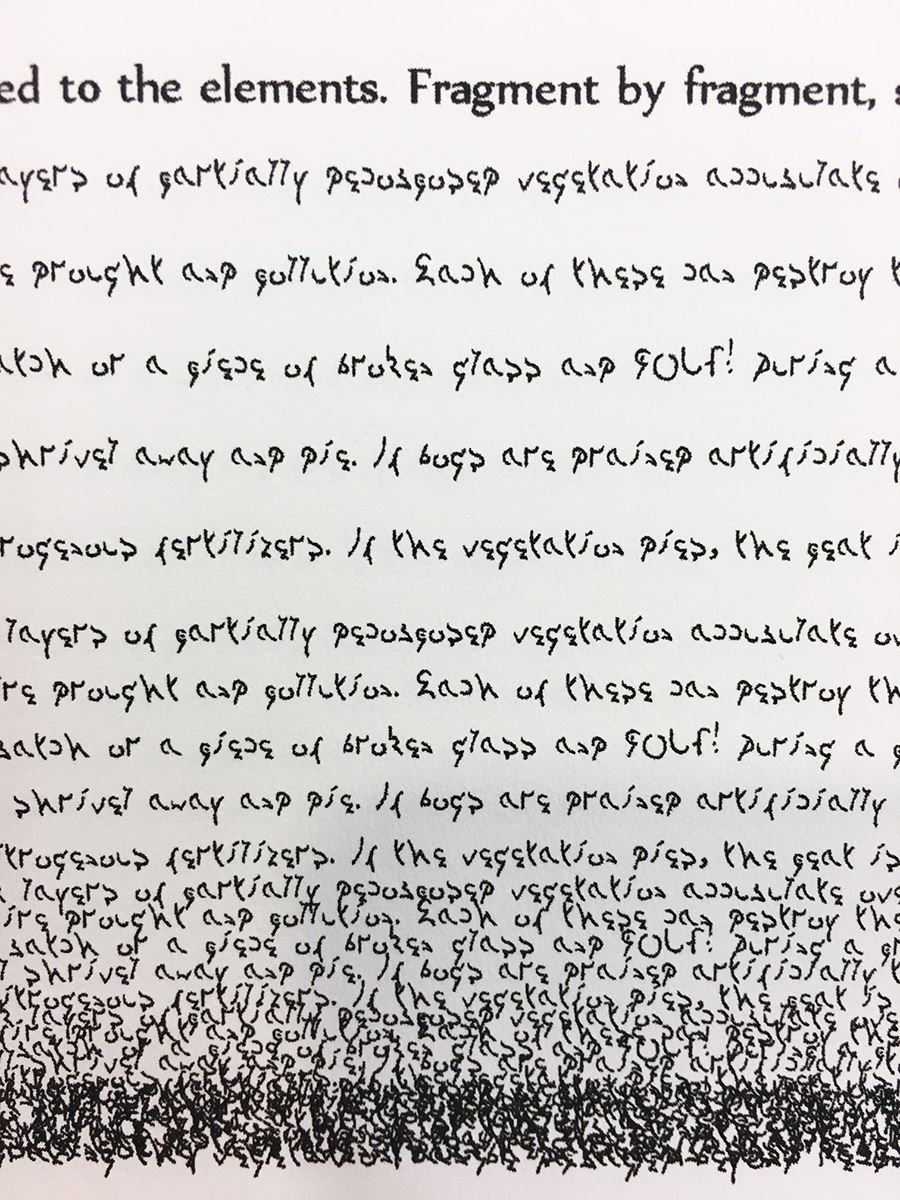

The bulk of Fragment is digitally printed in Peatbog, a font Charlston designed for the project.She describes the process in her artist’s statement: “I made hundreds of drawings of tiny fragments of peat. En masse, the drawings were transformed into a written language, obscure and unfathomable, reminiscent of Xu Bing's Book from the Sky.” Unlike Bing’s unreadable asemic marks, Charlston’s text is obscure but decipherable. Its legibility is challenging enough that the casual reader might give up. (It took me an hour to decipher a paragraph, so I was relieved to find the same text repeated throughout the book—the same landscape marked over time.)

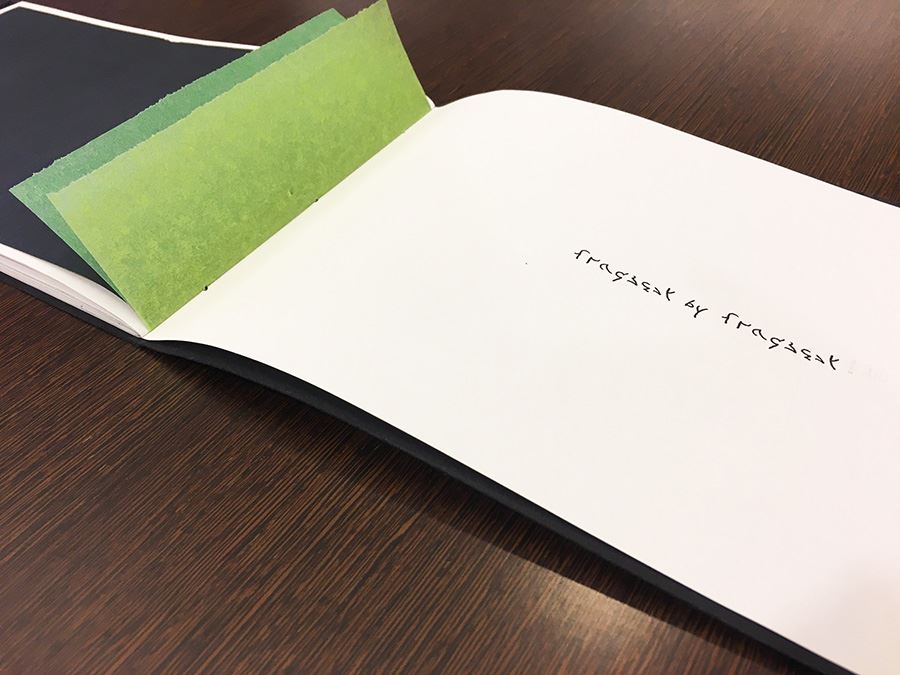

The book is bound as a pamphlet, opening into a 21” x 6” landscape format, upon which the erosion of the literal landscape of the peat bog is enacted. Two tissue end-leaves, in shades of green, overlay the first page of text. The tissue is fragile like the flora blanketing the peat bog.

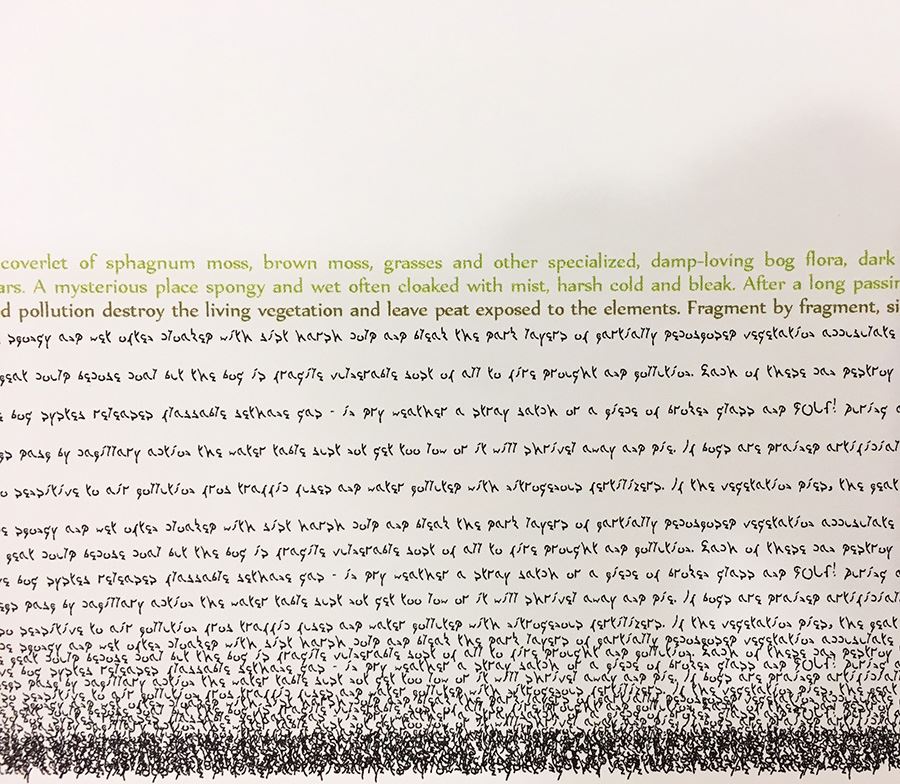

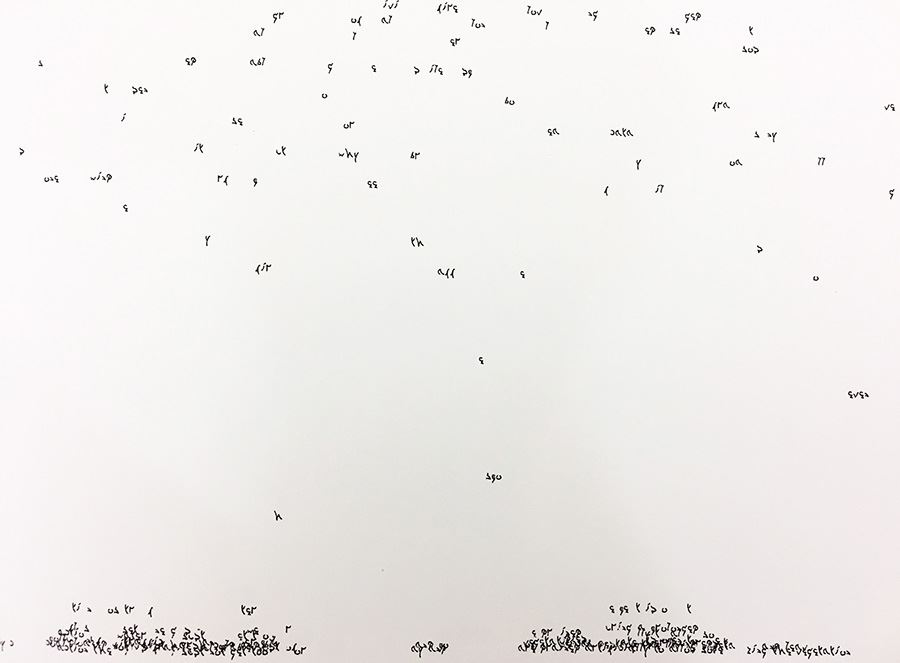

On the first spread, three lines of text in a clear roman typeface provide the ecological baseline of the peat bog narrative. These lines are printed in green and brown—representing the “coverlet of sphagnum moss, brown moss, grasses, and other specialized damp-loving flora” they describe. Below this are substrata of text, printed in black in the Peatbog font. This visual matter triples as language, micro-image (derived from drawings of peat fragments), and macro-image—an abstracted, representational cutaway of the bog.

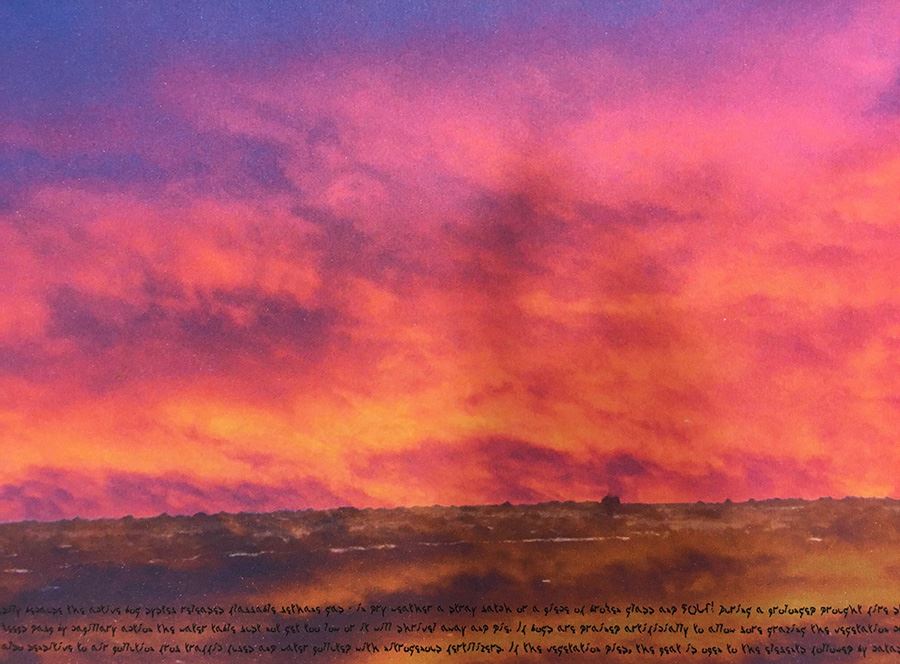

The second spread makes a radical visual shift: a photographic image of a landscape horizon and sky, printed in fiery orange and purple, bleeds off the edges of the page. The landscape appears charred and the atmosphere tumultuous. The saturated color, realism, and singularity of this image mark it as an important moment—the damaging fire referred to in the text, an event that precipitates a turn in narrative and ecological momentum.

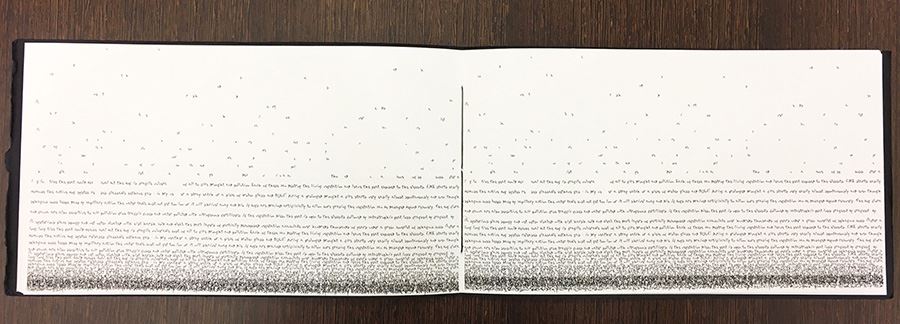

Ten subsequent spreads depict the systematic erosion of the landscape, with “signs” migrating from the tail to the head and off the page. The strata gradually deteriorate, with the final page being nearly blank. Aesthetically, there is nothing bothersome about this dissolution; on the contrary, as an abstract image the progress is pleasing—the pages well balanced with a predictable, almost meditative pace.

The anxiety of the piece stems from the tension between the work’s aesthetic values and its environmental critique. The peat (the signs, the meaning) is a resource. The difficulty of decipherment implies that attentiveness, research, and patience are key components in negotiating the complex of cultural, economic, and scientific factors affecting this resource. The problem can only be understood through careful study; in the meantime, the resource—wherein lies the very potential for understanding—dwindles.

Though the outlook appears bleak, a reader might encounter the turning of the final page with optimism. Following a solid black end-leaf, two fringes of delicate green emerge. The tabs of the tissue paper blanketing the initial page of the book could be simply a structural necessity, but the meticulousness of the book’s design suggest something more: new growth on the scarred bog. Furthermore, the repetition of the title at the end of the text suggests the book may be read backwards, reversing the erosion.

This blog post is adapted from a paper presented at the twelfth biennial conference of the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment.

Photos taken by the author in the Rare Book Department of Special Collections at the University of Utah’s J. Willard Marriott Library.

Emily Tipps is Program Manager and Assistant Librarian (Lecturer) at the Book Arts Program at the University of Utah, and the proprietor of High5 Press.