Unless you meditate you probably haven’t spent much quiet time just being with yourself, lately. But if you have, then you’ll know that quiet isn’t an absence but reveals the presence of the sounds you’re not listening for. If you’re like me, you don’t often hear the hum of household machines while cicadas chirp outside and the cat licks its fur because whatever media you absorb—New York Times and Washington Post apps refreshed every fifteen minutes— in order to try to keep up with what’s happening—or entertainment you subsequently take in—Spotify, Netflix, HBOGO, YouTube—in order to dam the overflow of bad news—whatever you choose to engage with is also incorporating your life within this larger, noisy entity we call Media and Entertainment (ME). When incorporated, the self gets blotted out and loses its identity in order for it to be en masse, as one, with the all.

This incorporation into the public is of course one way we get to the point of thinking of groups of people in monolithic terms. For example, ME has determined African American protest is loud and wild, crazy and passionate to the extreme. Take Colin Kaepernick, the now out of work NFL quarterback who peacefully, silently protested the treatment of African Americans by sitting and then kneeling during the national anthem. Trump and now Pence call names, taunt, threaten, and stage antics making this quiet, simple protest seem a radical, threatening gesture when Kaepernick and those who have since followed his lead make a simple sign that they will not be incorporated, they will not have their selves be uncritically absorbed in the wash of patriotism performed for the sake of making us silent.

I’ve been thinking about Kaepernick, quietness, and selfhood a lot because I recently had the good fortune of hearing Dr. Michelle S. Hite lecture at The College at Brockport, SUNY. Hite’s talk was on the denial of African American quietness, interiority, and dreaming. She cited Kevin Quashie’s Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture that uses, amongst other examples, Tommie Smith and John Carlos’s fist-raising protest at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics as evidence of the racist denial of black selfhood. As Quashie rightly notes, in the iconic image of the athletes on the podium, both Smith and Carlos have their heads bowed and eyes closed, a sign of quietude and interiority, a selfhood, that the public, that ME deny the existence of in African Americans. Photographs are far from facts and definitely mute but it is impossible to avoid what this oft-repeated image says about the interior minds of Smith and Carlos: that they are theirs and theirs alone. We don’t know what they were thinking but they are creating a quiet place in a loud and broad public to be with themselves.

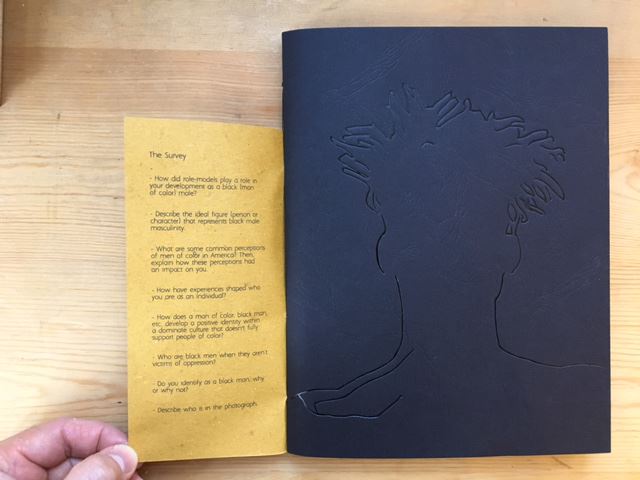

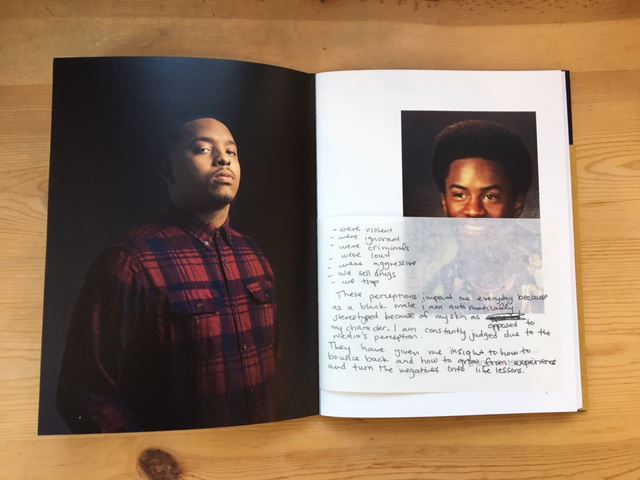

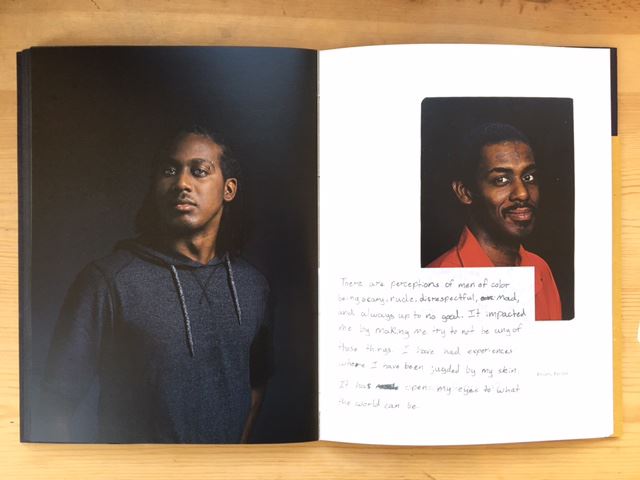

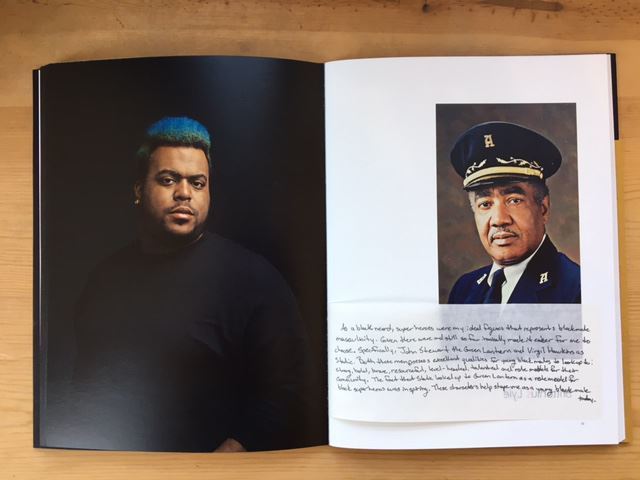

A stunning space to reflect on quietness, interiority, and self against the odds of its development is the photo artist’s book Come to Selfhood by Joshua Rashaad McFadden. For this remarkable book, McFadden made formal portraits of African American men including himself, paired them across the gutter with a vernacular image of their fathers, and between the two images, printed on soft, lightweight laid paper, answers to survey questions written in the hand of those photographed. When you see the stillness and strength of each man, see the brightness of their eyes, see the differences in their posture and features, see the likenesses with their fathers, you empathetically feel these men, individually. You question how people could ever be seen monolithically in terms of race or gender. But then you read the personal responses to the survey questions like “What are some common perceptions of men of color in America? Then, explain how these perceptions had and impact on you?” where one man, Keith Goins, responds:

“—we’re violent

—we’re ignorant

—we’re criminals

—we’re loud

—we’re aggressive…

These perceptions impact me everyday as a black male because of my skin as opposed to my character. I am constantly judged due to the media’s perception.”

And if you’re a white, regular ME ingesting man like me who is reading McFadden’s book, you might have a flash of observation that Goins’s father in the vernacular photo shows him to be particularly young. As opposed to it being a photo Goins selected because it represents his father to him personally, your instant interpretation of the image is that Goins’ father died young. He was probably shot and killed, you might think.

McFadden’s quiet book reveals what is present. I got caught, my own racism and gender biases exposed. But as Dr. Omi Osun Joni L. Jones has stated, getting caught is a good thing. “Exposure is a step toward freedom.” We need more books like Come to Selfhood. We need to support more artists like McFadden. You need to see and hear what is present in the quiet of this critically important book.

Tate Shaw is an artist and writer living in Rochester, NY. He is the Director of Visual Studies Workshop (VSW) and directs the College at Brockport, SUNY MFA in Visual Studies at VSW. Cuneiform Press published a collection of Shaw’s essays on artists' books, Blurred Library, earlier in 2017.