“Speed now, Book…A thousand hands will grasp you with warm desire…” —from the publisher’s note distributed with The Nuremberg Chronicle in 1493

Books are threshold objects. Even with their backs turned on us, spines out, they seem to beckon. Like unearthed artifacts, their appearance is charged with incipience, their small heft suggesting pockets of space and time a reader might re/enter through the conduit of her body (eyes peering, hands grasping, the theater of the mind set into motion). Both as symbolic objects and as experiences, books possess the allure of the real and expansiveness of the immaterial, marking a dilation of presence in absence.

The codex serves as metaphor for both embodiment and ensoulment. In her plaster casts of the negative space around shelved books, Rachel Whiteread evokes the ghost in the machine of the book, so to speak. In her room-sized Untitled (Paperbacks), we find hollows where the library’s volumes once were, the impress of fore-edges in the plaster like the postures of witnesses at Pompeii. Here the book represents a palpable break in the skin of the known.

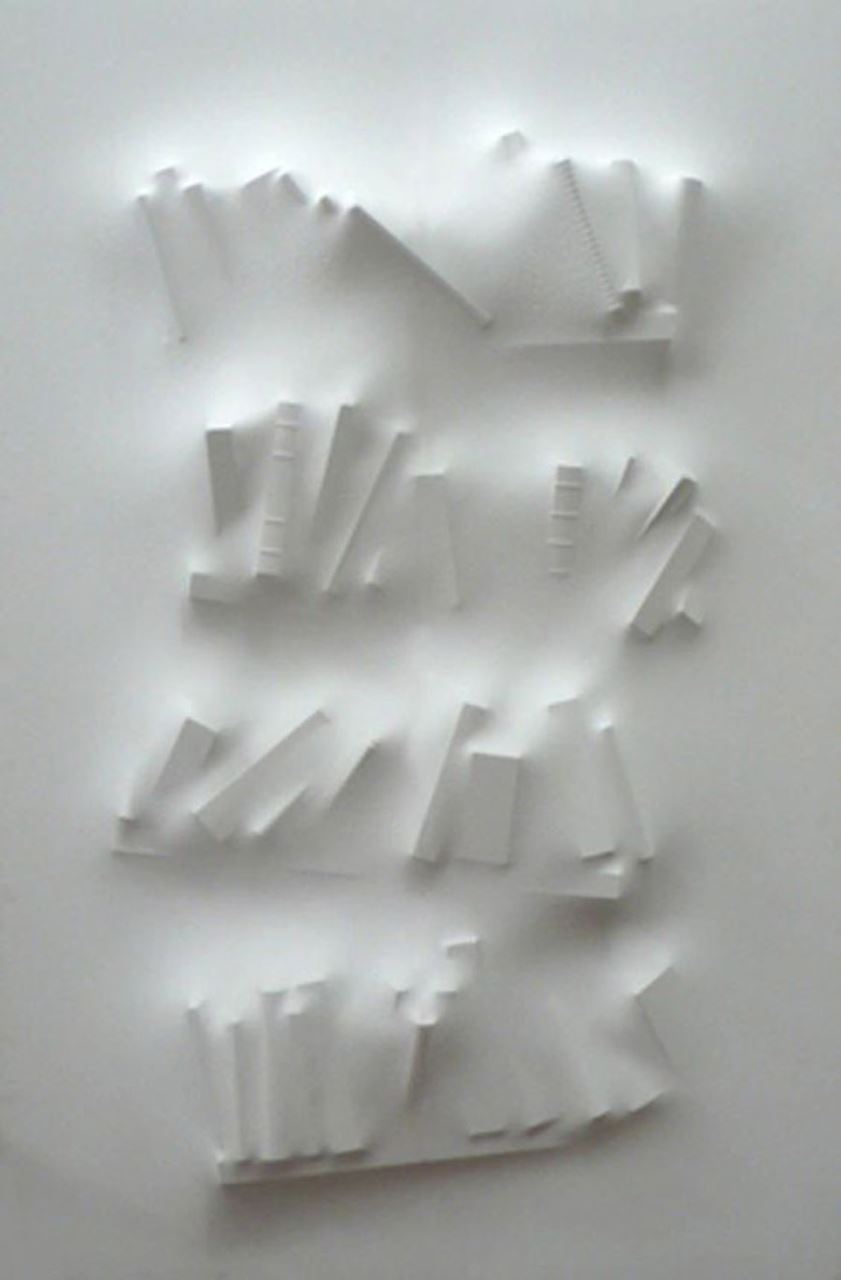

Gaps (books 1), Loris Cecchini, 2005

Loris Cecchini, in his Extruding Bodies series, also uses the book as a symbol for threshold states. Gaps (books 1), like Whiteread’s Untitled (Paperbacks), employs an all-white palette to lay bare what Cecchini calls “poetical distance”—a murky space of emergence into material being. Jumbled spines press against a skin of polyester, as if straining to tell their stories. There is a fragility yet stubborn insistence to this gesture, the bodies of the books limning a gap between the graspable and the ineffable. This urge to become, to emerge and persist, is one that all living things share; for us humans that urge extends to the persistence of memory, for which books are both medium and metaphor.

Alchemist's Handbook, Alexis Arnold, 2013

It could be argued a book only “becomes” in the mind, its contents crystalizing moment by moment in the imagination. But what if a book lies fallow, unread? Alexis Arnold addresses the transience and vulnerability of the physical book in her artwork. She collects discarded paperbacks, transforming them into colonies of borax crystals. She speaks of this almost as an intervention, an attempt to immortalize the body of the book by replacing inert text with living crystals. “The books,” she writes, “become artifacts or geologic specimens imbued with the history of time, use, and nostalgia.”

Books themselves may be time capsules of personal and cultural memory, intended to extend knowledge beyond one lifetime, but in the artwork discussed here, it’s the very bookness of the book that matters most, not its contents. The suggestion of its form is enough to provoke reverie or something bittersweet, a pang of loss. Even when closed, a book offers a kind of window, a glimpse beyond, as well as silent witness. Saskia Hamilton captures this threshold quality in her beautiful poem from 2014.

Zwijgen

I slept before a wall of books and they

calmed everything in the room, even

their contents, even me, woken

by the cold and thrill, and still

they said, like the Dutch verb for falling

silent that English has no accommodation for

in the attics and rafters of its intimacies.