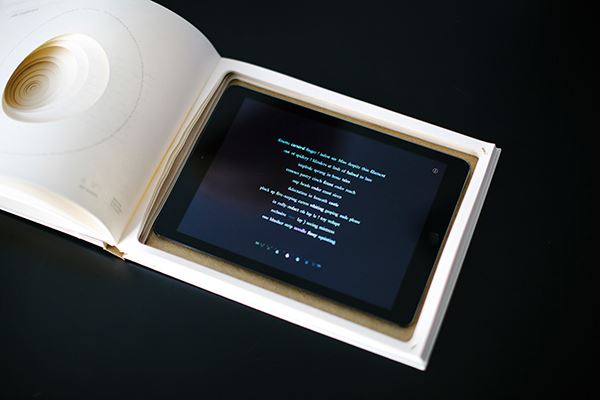

At the Center for Book and Paper in Chicago, an initiative devoted to creating “expanded artists’ books” presents transmedial works that bridge what we would consider a traditional artist’s book—the concrete, physical, haptic art object—and the digital, like an iPad/iPhone application (Abra by Amaranth Borsuk and Kate Durbin with Ian Hatcher). In these projects, old and new media deliberately link arms to declare their shared investments, investments I think of as key to artists’ books in any guise: material and formal considerations embedded into materiality and form; reading as a vibrant and immersive experience; writing that develops in tandem with its medium, shaping and being shaped by it.

For digital and new media scholars, reading this kind of writing begins with N. Katherine Hayles’s concept of “media-specific analysis.” In her now-classic essay “Print Is Flat, Code Is Deep,” Hayles argues that we must read the materiality of texts, hypertexts both digital and print, as well as their semantic content. She characterizes materiality as “the interplay between a text’s physical characteristics and its signifying strategies”—such medial self-awareness, she acknowledges, hardly limited to digital examples (72). Many of these examples, in fact, reference “reverse remediation” in digital hypertexts, moments where the digital mimics the analog: the appearance of dog-eared pages in print codices transferred to a screen; the illusion of something like Scotch tape at the edges of ersatz photographs; the moments which, as Emily Larned wrote in an earlier post for this blog, often create an “aesthetics of interference,” where such interference is constructed for the comfort or delight of the reader. This is not a new reaction, of course: we could cast much further back to recall the moment where moveable type, as blackletter, mimicked the script to which readers had been accustomed.

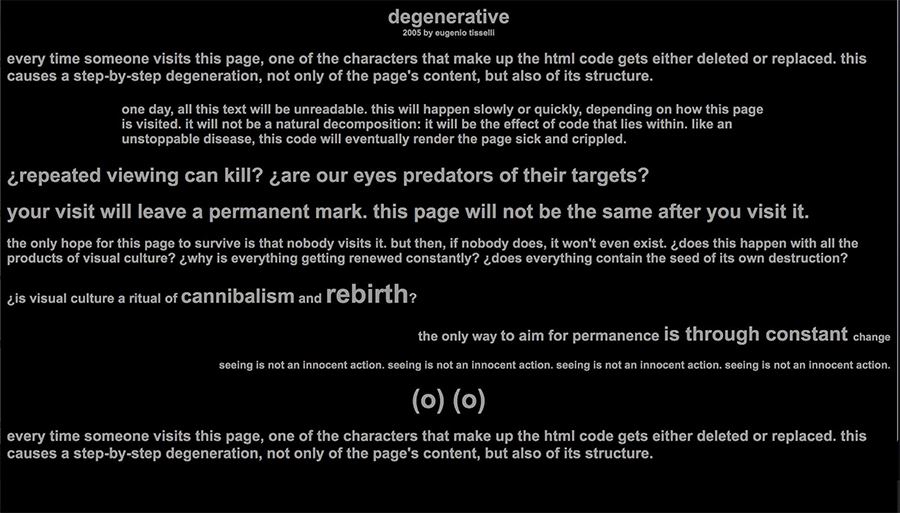

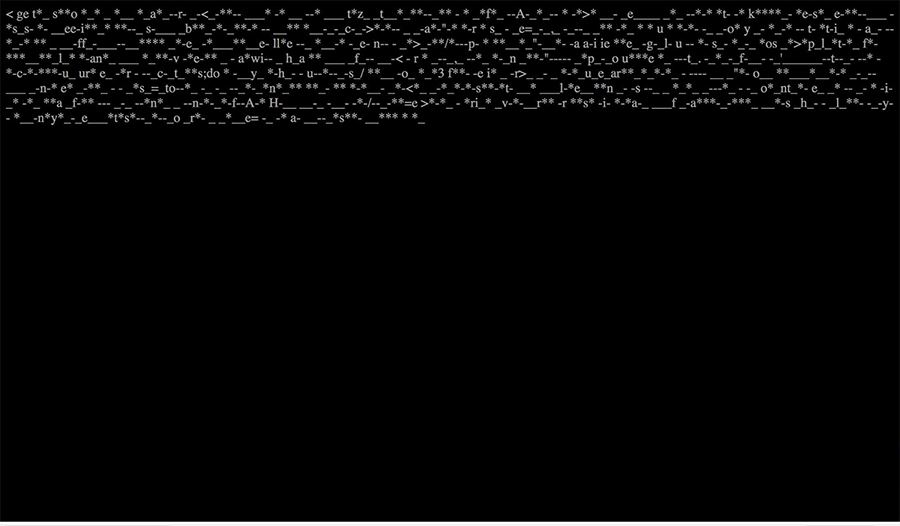

Digital and new media scholars, both Hayles and those who follow, are far from allergic to more traditional artist book examples (see Hayles’s Writing Machines, which references Tom Phillips’s classic A Humument, or Manuel Portela’s Scripting Reading Motions: The Codex and The Computer as Self-Reflexive Machines, which has a chapter on Johanna Drucker’s letterpress work). Yet those with an interest in artists’ books often overlook the digital. At the Electronic Literature Organization conference in Portugal this summer, I heard about projects ranging from Taiwanese artist Hsia Yu’s book of digital remix poetry printed on Mylar, Pink Noise; to Rote Bete, a book made entirely on the copier by Portuguese artist César Figueiredo; to Eugenio Tisselli’s “Degenerative,” a web-based project which was corrupted bit-by-bit every time it was visited.

Page from Rote Bete

Yu’s book might easily be assimilated into the genre of artists’ books, perhaps Figueiredo’s work as well. What about Tisselli? Does it change our view to know the degenerative process was captured at various stages of decay before fading away completely, again suggesting, to an artist’s book reader, strange parallels with flux that might have intrigued Tom Phillips?

Day 1 and Day 44 of “Degenerative”

The truth is, of course, that both print and code are equally deep (or equally flat—take your pick). After all, both digital and analog are material. As Matt Kirschenbaum argues in his fantastic 2008 book Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination, it’s a convenient illusion that the digital is “hopelessly ephemeral...infinitely fungible or self-identical, and that it is fluid or infinitely malleable” (50). Instead, Kirschenbaum reminds us, “Every contact leaves a trace” (ibid). Why should we not extend our consideration from artists’ books to the digital, then, especially given their shared concerns about media specificity, self-reflectiveness, and reading?

In its digital guise, Abra, which I mentioned at the beginning, encourages the user to create new poems through casting “spells” on the screen, which can shift and mutate words, graft the user’s words into the evolving poem, erase words from the lexicon, all in a shimmering set of rainbow hues. There is a paperback version, as well, that does not attempt to replicate the app but instead extends its concerns to another form. And linking the two is a letterpress-printed, small-edition handmade codex. At the back of this book there is a space left for an iPad, inviting the user to make the connection.

Abra, from the Center for Book and Paper Arts’s website

Works Cited

Hayles, N. Katherine. “Print Is Flat, Code Is Deep.” Poetics Today 25, no. 1 (2004). pp 67-90. doi: 10.1215/03335372-25-1-67.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2007.

Anne M. Royston is a Visiting Assistant Professor in English at Rochester Institute of Technology. She received her Ph.D. in Literature, as well as a Book Arts Certificate, from the University of Utah. She is a founding member of the Salt Lake City-based independent book arts group, Halophyte Collective.