The typical codex allows the reader a single, fixed point of view, while the accordion offers the reader, both literally and metaphorically, a panorama of viewpoints. I want to explore some other avenues through which to approach the accordion, namely the domestic sphere and the body.

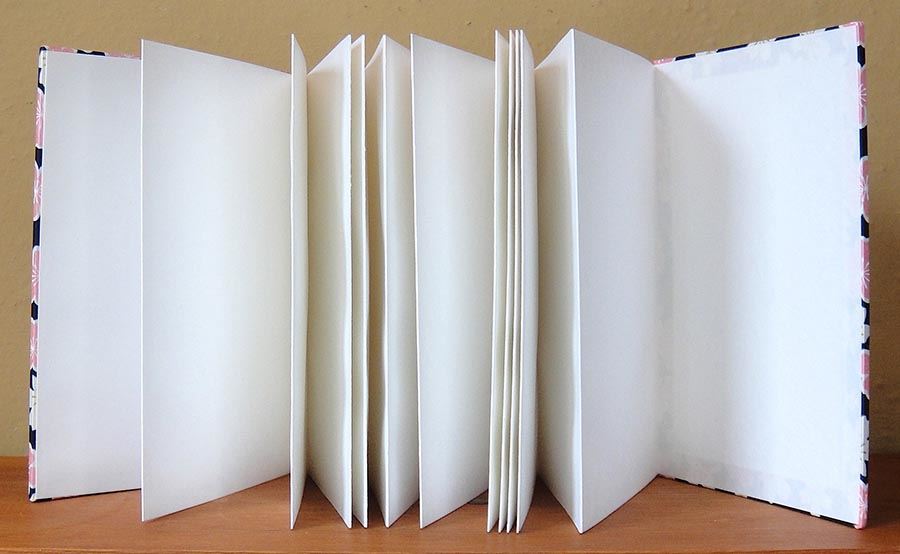

An accordion is a length of paper with alternating equidistant folds that create parallel uniform-sized sections or pages, often with front and back covers or a protective sheath.

Anne Boyer, in a review of the artist Hannah Wilke’s recent retrospective [1], addresses the centrality to her practice of what Wilke called her “one-fold gestural sculptures”[2], which were small vulva-like folded works that were made from a variety of materials. Boyer, in a particularly lucid response to Wilke’s folded works, inquires into the nature and definition of the ‘fold’ itself:

“Folding is the gestural equivalent of paradox, in that it takes what had neither inside nor out and, without transforming its substance, gives it both. Before a flat plane is folded, we know it as surface — superficial, exposed. Once a flat plane has become a fold, the same material becomes an intriguing half-secret — the fold alerts us to the once clandestine affordance of surface." [3]

Boyer continues, examining the broader landscape in which Wilke’s folded works are located, and notes the following:

“Important too to Wilke’s work is that the fold is a gesture linked to feminized labor, what was once understood as ‘women’s work’: doing laundry, diapering, preparing dough. The efficiency of the fold, done over and over, mimics the ongoingness of folding as care work, while it simultaneously creates mystery out of shallowness, dimensional form out of apparent flatness.” [4]

In opening up the activity of folding through the concept of ‘feminized labor’ Boyer also broadens the larger terrain within which folding is located. It becomes clear that folding, as in folding newspapers, letters, dish cloths, napkins, clothes, and all the other myriad things we fold, is an activity deeply embedded, but largely unnoticed, within our everyday lives.

Brendan Murphy, Folding Linens, oil on wood panel, 2019.

Locating the domestic sphere as an active site of folding links it to another term for the accordion. Leporello is named after the character in Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni (1787), in which Don Giovanni's numerous seductions are exposed by his manservant Leporello, who produces an accordion style list that unfolds to reveal 2,064 names. Leporello’s choice of the accordion format was wise, as the accordion is eminently suitable for economically organizing large or small amounts of information for storage and retrieval. No doubt we have all made shopping lists and folded them to make them more manageable.

The term leporello, with its German and Italian origins, has more currency in Europe. In the United States, the preferred term remains accordion, with its own musical connection. The accordion’s innate ability to expand and contract, to fold and unfold, is derived from the opening and closing of the pleats of the bellows of an accordion, which can be likened to that of breathing for a singer.

The accordion’s often unwieldy length presents the reader with both a physical and intellectual challenge. To hold, and then open, an accordion is to enter into a unique visual and literary relationship with a sculptural object. Closed, an accordion functions as a discrete book-like object and can be read page by page, like a codex. But once opened, it requires spreading one’s arms in a kind of open embrace to take in the measure of the body of the accordion. Add the breath-like expansion and contraction of its folds, and an encounter with an accordion is shaped by a unique physical intimacy.

In these intimate interactions, we must fold the accordion into our body to ensure its safety. And, like Hannah Wilke's folded vulvic works, our encounters with accordions make us aware of how our own bodies, with their sheath of endless folds, protect and nourish us.

1] Anne Boyer, “Living as Art,” Art in America, September/October, 2021, pp. 38–47. The exhibition was: “Hannah Wilke: Art for Life’s Sake,” Pulitzer Arts Foundation, Saint Louis, 2020–2021.

2] Nina Renata Aron, “Hannah Wilke’s ‘labial’ artwork challenged both the patriarchy and feminists,” https://timeline.com/hannah-wilke-labial-art-97c5bc488a67, accessed March 21, 2022.

3] Boyer, p. 40.

4] Ibid, pp. 40–41.

Stephen Perkins is an art historian, curator, and artist living in Madison, Wisconsin. He is the curator of the home gallery Subspace.